Minimization (The Rope Cutting Problem)

If you’re in secondary school, chances are you’ve had to discuss a bunch of properties of functions. These include finding the maxima and minima, the roots (zeros), the intervals where the function is positive or negative, the intervals where the function is increasing or decreasing, and the domain of the function. While having to slog through page after page of this, you might be tempted to ask, “Why do I have to learn about this? Not only is it boring, it’s completely useless!”

Trust me, I hear you. The problem is that, through doing countless exercises of the same flavour, you gain proficiency, but you don’t learn why you should have this piece of information. To remedy this, let me give you a problem where knowing the properties of a function are quite useful. I came across this problem while watching some videos by the great mathematics teach Eddy Woo, and I think if you’ve been wanting something a bit more than what you’ve done in your classes, this will be interesting to you. I’ll state the problem, and then I’ll explain the solution. As such, if you want to try the problem beforehand (which I recommend!), stop reading after I state the problem.

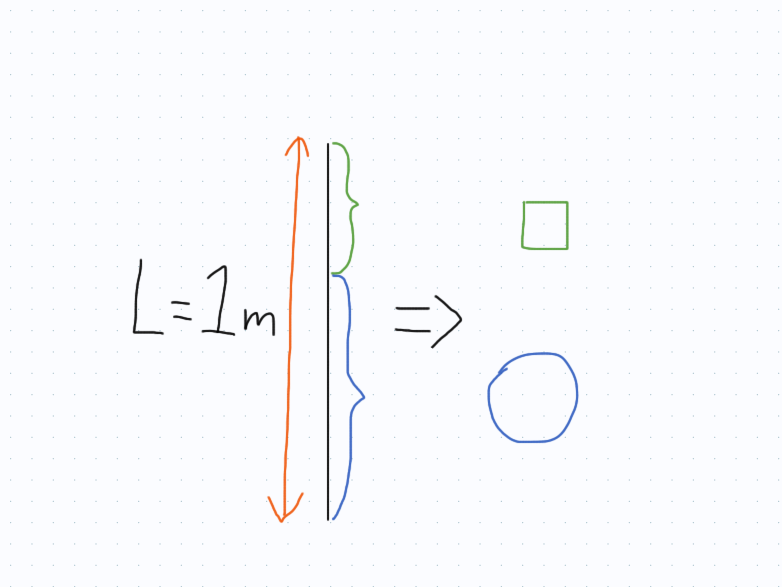

Problem: Imagine you have a one metre rope. Your task is to decide where to cut the rope in order for the two pieces of rope to make a square and a circle. Where should the cut be made in order to minimize the combined area of the two shapes?

Solution:

Begin by choosing a variable to represent the problem. For the square, we have the potential variable $s$, which is the side length of the square. For the circle, we have the natural variable $r$, which represents the radius of the circle. Either variable will work, but only one is needed, since we can express one variable in terms of the other. For this solution, $r$ will be used.

We want to minimize the total area of both shapes, so we need a function that gives us the area. Since we know what the area of a circle is in terms of $r$, and what the area of a square is in terms of $s$, we get the following area function:

\[\begin{equation}

A = \pi r^2 + s^2.

\end{equation}\]

Obviously, this has two variables in it, $r$ and $s$. However, as we mentioned above, we can express one variable in terms of the other. This is because the variables $r$ and $s$ can’t be anything. They are constrained by the fact that the rope given in the problem is only one metre long. In other words, the length of the rope has to be the sum of the perimeters of the two shapes, since that’s exactly what the rope will be used to create. Therefore, we get the desired constraint.

\[\begin{equation}

1 = 2 \pi r + 4s \implies s = \frac{1}{4}(1 - 2 \pi r).

\end{equation}\]

Now that we have the variable $s$ expressed in terms of $r$, we substitute this into Equation (1).

\[\begin{equation}

A = \pi r^2 + \frac{1}{16}(1 - 2 \pi r)^2 = \frac{1}{16} \left[ (16\pi + 4\pi^2)r^2 -4\pi r + 1 \right].

\end{equation}\]

The question now becomes, “Where is this a minimum?” To answer this, you might wonder if there is a minimum, but after a moment’s reflection you should recognize that Equation (3) is the equation of a parabola with a positive coefficient for the $r^2$ term, meaning the parabola makes a “U” shape and so does have a minimum. To find the minimum, we will use two different strategies.

The Calculus Way

If you know a bit of calculus, you might be tempted to take the derivative and set it equal to zero (since a parabola only have one point where the derivative is zero). Doing so gives the following.

\[\begin{equation}

\frac{dA}{dr} = \frac{1}{16} \left[ 2(16\pi +4\pi^2)r - 4\pi \right] = 0 \implies r_{min} =\frac{1}{8 + 2\pi}.

\end{equation}\]

This gives us the radius at which the total area is a minimum. Therefore, if we want to know where to cut the rope, we want to know the circumference of the circle (since that will indicate where the cut should appear). This means the we need to cut the rope at $2\pi r_{min} = \frac{2\pi}{8+2\pi} = \frac{\pi}{4+\pi}$, which is approximately 44% of the rope.

Completing the Square

The second way to solve this problem once we have Equation (3) is to complete the square. Doing so will transform Equation (3) into the “standard form” of a quadratic equation, which looks like $f(x) = a(x-h)^2 + k$. From there, we know that a quadratic equation has a minimum or maximum at it’s vertex, which is given by $(h,k)$. Therefore, all we need to do is find the coordinate $h$, and we’ve got our minimum. To do this, we will just label the coefficients of Equation (3) as $a$, $b$, and $c$, so we get the following:

\[\begin{equation}

A = \frac{1}{16} \left[ (16\pi + 4\pi^2)r^2 -4\pi r + 1 \right] = ar^2 + br + c.

\end{equation}\]

To complete the square, we first have to factor the $a$ from both the $r^2$ and $r$ terms, giving:

\[\begin{equation}

A = a\left(r^2 + \frac{b}{a}r\right) + c.

\end{equation}\]

Now, we simpy write what is in parentheses as a perfect square, and subtract off the extra part. This gives:

\[\begin{equation}

A = a\left( \left(r + \frac{b}{2a} \right)^2 - \frac{b^2}{4a^2}\right) + c.

\end{equation}\]

Cleaning up these terms brings us to the standard form:

\[\begin{equation}

A = a\left(r + \frac{b}{2a} \right)^2 + \left(c - \frac{b^2}{4a} \right).

\end{equation}\]

If we recall what our coefficients were, we see that $a = \frac{16\pi + 4\pi^2}{16}$ and $b = \frac{-4\pi}{16}$. From Equation (8) above, we know that our coordinate $h$ is $-b/2a$ (remember that the standard form of the equation has $-h$ in it), so we get:

\[\begin{equation}

h = \frac{4\pi}{2(16\pi + 4\pi^2)} = \frac{1}{8 + 2\pi} = r_{min}.

\end{equation}\]

Once again, if we want to find the spot to cut the rope, we need to multiply this result by $2\pi$ (to get the circumference of the circle). Doing so gives us once again $\frac{\pi}{4+\pi}$, which is about 44% of the rope.

Hopefully, you were able to solve the problem. I really like this problem because you need to come up with your own variables and you need to know how to find the minimum of a function, which are things you might practice a lot, but never really use in a problem. As such, I wanted to give you a taste of what these function properties can actually help us with.

Happy problem solving.