Premature Wielding of Mathematical Tools

As a physicist, mathematics is the language I speak. It’s what I use to discuss physics, and I’m familiar with many of the tools that mathematicians learn. The tools range from the fields of calculus, probability, statistics, linear algebra, differential equations, graph theory, and many others. In particular, solving differential equations is like the bread and butter of physics, so I’m versed in this area. Knowing how to untangle the Schrödinger equation or the field equations in general relativity is a skill that physicists pick up during their education.

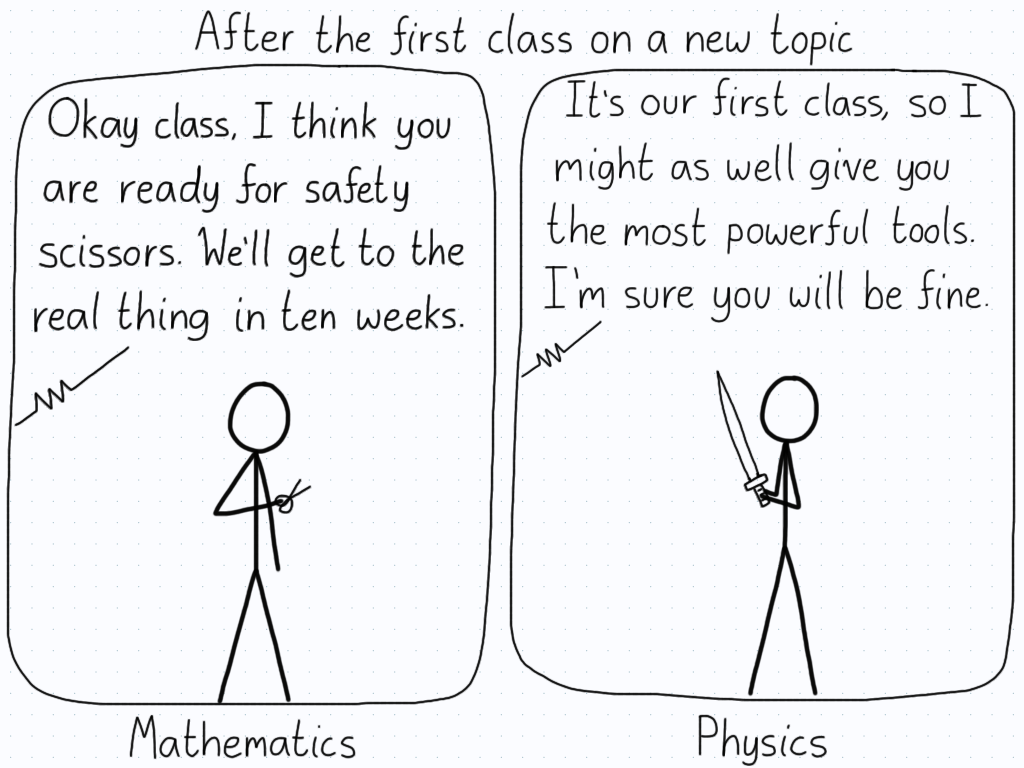

And yet, I can’t help but think of my education in wielding mathematical tools in the following way:

In my experience, “crash courses” on how to use a mathematical tool in a physics class are not uncommon. These involve the professor spending a few minutes to review the operational nature of the mathematical tool, and then jumping right into how this is applied in physics.

I can’t begrudge the professor for doing this. After all, it shouldn’t be their responsibility to get the class up to speed with a mathematical tool. Instead, the students should have some background before coming to class and learning how these are applied to physics. For me, this has been an incredibly frustrating experience at times.

For example, during master’s program, I had to ramp up my knowledge in physics to follow along in the courses. This meant I had to learn the mathematical tools necessary for these courses. I remember being super confused by the notation and tools we were using in our quantum theory course. During my undergraduate degree, I hadn’t ever seen density matrices and didn’t really use the bra-ket notation that I was now seeing everywhere. Suddenly, I had to make the big jump in understanding a lot of these mathematical tools that I hadn’t been introduced to. To make matters worse, I had to learn this on an operational level, without the mathematical background.

For someone who hasn’t studied mathematics, this might seem fine. After all, most of us don’t know how the internet works, or even how most of the machines in our day-to-day lives function, and yet we don’t worry about it. We don’t force ourselves to know the inner workings of a toaster before using it to heat our bread, so why should we need to know every little thing about the mathematics?

To a physicist (and others) who need to use the tools from mathematics for tackling their problems, this is a big deal. That’s because the tools aren’t always used in the same way, and knowing their limitations can help with exploring new ways to solve problems. Take out the background knowledge, and all you’re left with is a tool that you know applies to a particular situation.

Mathematical background for a tool gives you context for how to use it in a variety of scenarios.

I was able to get through the quantum theory course, but I would be lying if I said I understood the nuances of what I was doing with the mathematics. I was wielding the tool, but as an operator, not a master.

I don’t know if we can fix the problem. Simply adding more mathematics courses to the workload of students won’t work, since their schedules tend to be full. Instead, I’ve been thinking about how we can live with this issue, particularly as physicists.

Let’s face it: while many physicists (particularly theoretical physicists like myself) enjoy mathematics, we aren’t driven solely by it. We want to actually apply our tools to a problem, sort of like how I imagine an engineer enjoys the principles of physics but wants to apply them to create things. As such, we might not have time or the desire to go through a bunch of textbooks to learn the ins and outs of a tool. So how can we move forward?

For myself, I want to take the minimalistic approach. If I come across a concept I need to understand, I look it up and try to grasp its mathematical structure. I then continue with my problem. I don’t try to know everything there is to know about the tool and its related concepts. I focus on what is necessary, and allow myself to live with that.

What I try to avoid though is solely using the “physicist’s approach” to a mathematical tool. While it’s usually operational, I rarely come away with an understanding of how to apply the tool to the next problem. That’s my big issue, and it’s why I want to seek out more mathematical sources in the future when learning a topic. If I can get past wielding the mathematical tools in a merely operational manner, I will consider that a success.

I think physics students are sometimes given tools without knowing what lies within them. This is fine if that distinction is made clear, but it needs to be made. Their should be an invitation for students to dive deeper. In my case, I found it difficult to apply these tools to new situations because I wasn’t comfortable with the tool. I suspect more mathematical background would help ease this discomfort.

It’s something I keep in mind each time I learn a new topic now. Am I only learning the operational approach? Am I okay with not knowing everything? And finally: Can I wield this tool well?