We might have lost the basketball game, but as a coach, it was one of the most inspiring performances I’ve seen from my team.

We had no business winning. Though we were good, this team was undefeated despite playing some of the other top teams in our league. As I watched our opponents move like athletic machines during warmup, I wondered if I was going to witness a bloodbath. But my team was undaunted. I could tell you about how we played physically, how we shot better than we had all season, how we kept the game close, and how we locked down on defense. But it would be easier to just say, “We played with belief.” If we hadn’t, we wouldn’t have just played average; the other team would have demolished us. We may have lost, but because my players believed in their skills and experience, they made it a much closer game than many would have predicted.

Belief isn’t just for sports. In my view, it’s a vital ingredient for creating change and making progress on some of the biggest problems we face. But this belief cannot grow out of nothing; it needs to stem from substantive data, reasoning, and knowledge. Otherwise, it’s easy to just sit back and let someone else solve our problems. The wrong kind of optimism is a liability, but the right kind propels us forward.

Getting the knowledge requires people doing the difficult work of digging through the scientific record, gathering data, and synthesizing it. It requires people like Hannah Ritchie, the Deputy Editor and Lead Researcher at Our World in Data, a non-profit that’s frankly a jewel of the internet for data exposition about the world’s problems.

As someone who has degrees in geoscience, carbon management, and global food systems, you might think that of course Hannah would be the kind of person to be optimistic. And she is, but that wasn’t always true. In her new book Not the End of the World, Hannah writes about her early universities years:

“In 2010 I started my degree in Environmental Geoscience at the university of Edinburgh. I showed up as a fresh-faced 16-year-old, ready to learn how we were going to fix some of the world’s biggest challenges. Four years later, I left with no solutions. Instead, I felt the deadweight of endless unsolvable problems. Each day at Edinburgh was a constant reminder of how humanity was ravaging the planet.” (Introduction)

She almost quit environmental science because doom dominated her worldview. After all, what’s the point in working in an area when you believe your efforts are futile? But then Hannah watched Hans Rosling present on metrics of human well-being, which changed everything for her. Rosling was showing how the world was actually getting better in many meaningful ways (such as the fraction of people living in extreme poverty and the estimated fraction of newborns that die before the age of five each year).

From there, Hannah began digging into the data more. She began zooming out, looking at historical trends instead of only reading the news. She took a job at Our World in Data, and her work over nearly a decade has led to this book.

Meeting the needs of the present and the future

Before we dive into any of the many metrics of progress that Hannah presents in her book, we need to agree on what we’re even striving for. Hannah’s book is all about sustainability, so she begins by sharing the definition of sustainability from a 1987 United Nations report: “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. In other words: we need to be good citizens and ancestors. I like this definition because it brings in more complexity and nuance than simply focusing all of our efforts on climate.1

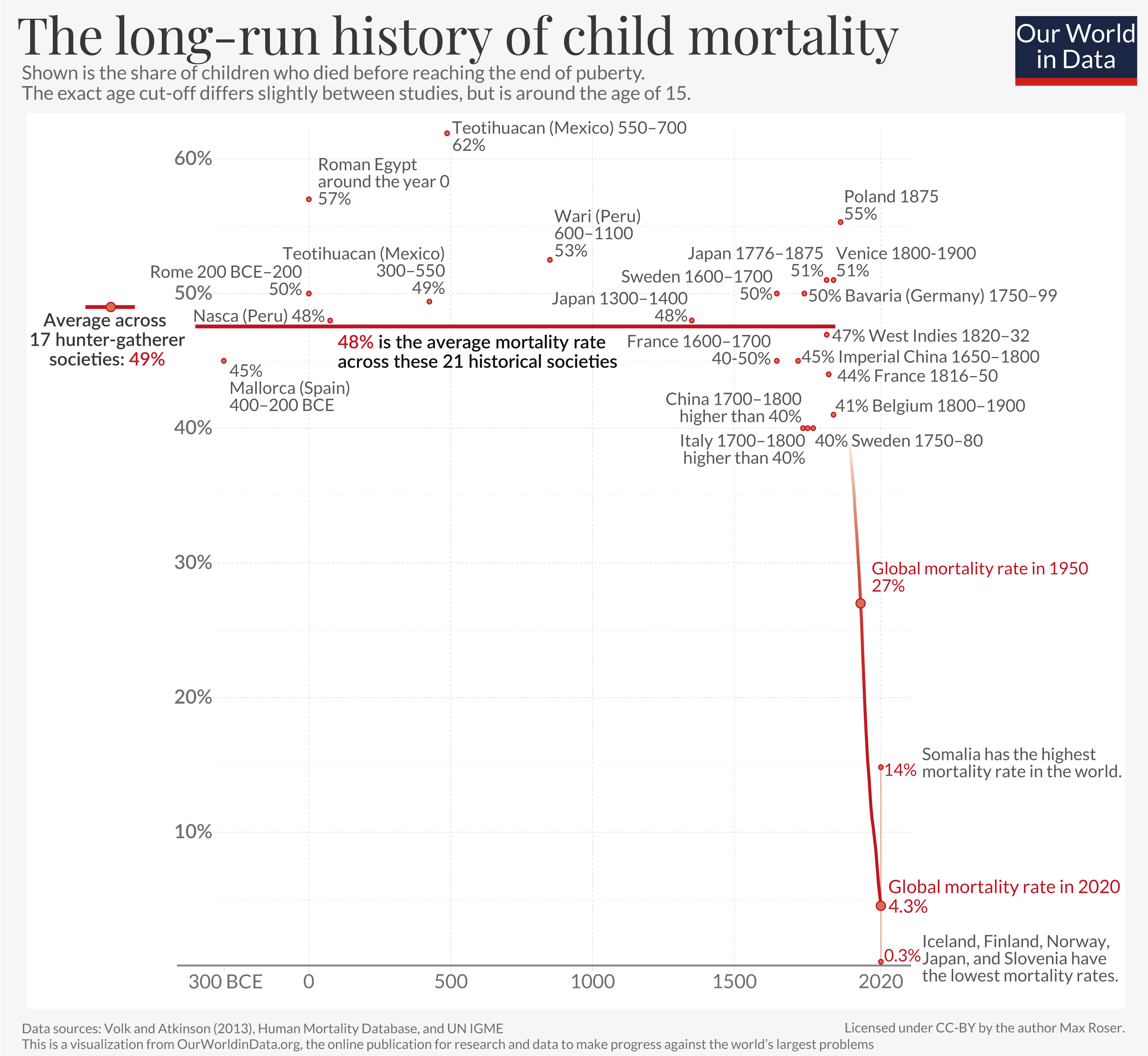

Hannah writes that we’ve always been missing one of the parts of sustainability. For most of human history, we didn’t have the luxury of thinking about the future. Survival was the priority. As Hannah says, “The majority of us think there’s a natural order to death: it’s the old not the young that die. But this sequence is a very recent development.” Take a look at child mortality over history:

We just weren’t living long, so if we could eke out extra time, we did. The high mortality rate suppressed the world population, limiting our impact on the planet.2 For a long time, we burned wood to give us energy, then many people moved to fossil fuels, which unlocked higher standards of living than ever in human history. We achieved the first pillar of sustainability for some.

But two issues emerged. First, a large fraction of the world still didn’t have access to this higher standard of living. And second, the massive increase in population and use of fossil fuels together have led to jeopardizing the needs of future generations. If we want to become sustainable, we need to address both issues.

In Hannah’s view, we actually have a chance at becoming the first sustainable generation. This isn’t just an optimistic perspective, but one based on looking at the long-term trends in human history. When you zoom out, you see that while the world is still terrible in many ways, it’s much better than in the past. And this context is crucial for grounding our worldview and bolstering our confidence that we can tackle the challenges facing us today.

In each chapter, Hannah develops our worldview by studying the past, present, and possible futures for seven big problems: air pollution, climate change, deforestation, food, biodiversity, ocean plastics, and overfishing. She tells us what we used to do, what we currently do, and what we could do. Hannah’s ability to look at a problem and not despair, but go into solution-mode is why I really enjoyed reading Not the End of the World. (This underlying spirit is also why I think Vox named her one of their Future Perfect 50 in 2023.)

Instead of going through each problem sector that Hannah presents, I want to bring out some key threads that weave through the entire book and have shaped how I now think about these problems.

Decoupling

“Is economic growth bad for sustainability?”

For a long time, I probably would have agreed. It seems reasonable: we really kicked off our economies on the back of fossil fuels in the late 19th century, and we’ve continued ever since. It would be a small jump to then say economic growth and fossil fuels are coupled, meaning growth would always be a bad thing for our planet.

And yet, I’d be wrong. In my view, Hannah’s most important idea in the book is that of decoupling our economic growth (and living standards) from environmental destruction:

“And it’s true that in a world without technological change, we’ll be stuck with fossil fuel power, petrol cars and inefficient homes. But as the chapters that follow will show, new technologies are allowing us to decouple a good and comfortable life from an environmentally destructive one. This is what makes it possible for us to be the first generation. In rich countries carbon emissions, energy use, deforestation, fertiliser use, overfishing, plastic pollution, air pollution, and water pollution are all falling, while these countries continue to get richer.” (Chapter 1)

It’s also not just a matter of sneaky accounting where one country “stashes” their environmentally destructive activities in other countries (though Hannah does write that this happens). Rather, as countries grow richer, they have more possibilities for how they power their activities. This gives us a chance at reducing our impacts. For Hannah, the big question is, “whether we can decouple these impacts fast enough.”

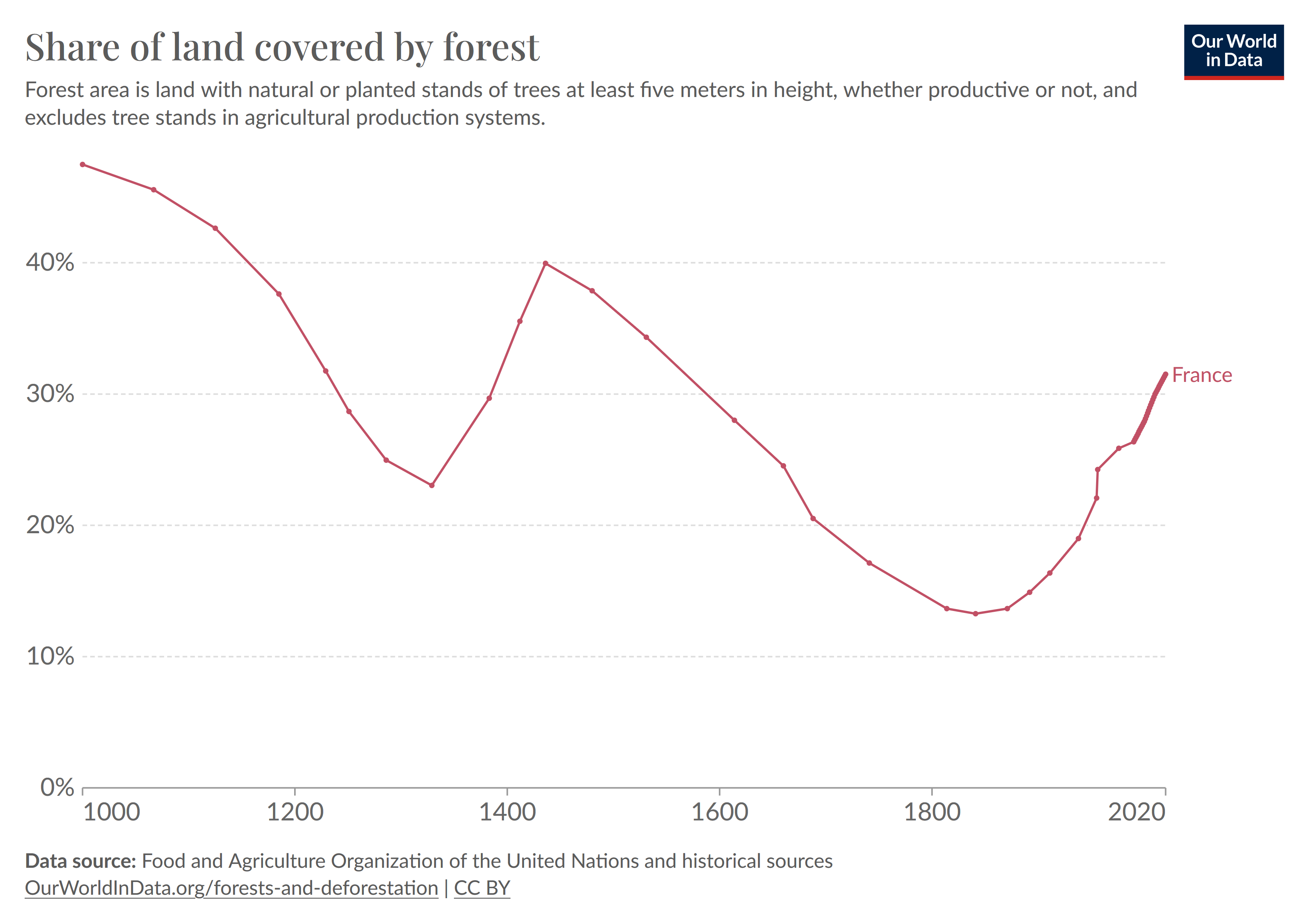

I want to show you two examples of decoupling in action. The first is deforestation. In Chapter 4, Hannah uses France as a microcosm of the history of humans chopping down trees for construction, energy, and farmland. The following chart captures the whole saga:

In the year 1000, forests covered about half of France. During the next three centuries, the population doubled (8 million to 16 million). The result is that the people of France needed a lot more timber and energy, so they chopped down about half of the forests (leaving ~25% of the area in France as forests).

You then see a dramatic increase in forests during the next century or so. That’s because of the Black Death, which reduced France’s population to 10 million. Forests grew back as there was less of a need for timber, energy, and farmland.

But this restoration was only temporary. Midway through the fifteenth century, France’s growing population begins depleting the forests again. France needed wood for ships, land to grow crops (with very low yields), and energy for heating and powering industries. As Hannah writes, it would be easy as a person living in 18-century France to conclude that your home would soon be devoid of forests.3

From our vantage point in time though, we can see that this conclusion would be very wrong. Look at the rebound starting in the 1800s! The fraction of forested area in France made a U-turn, and most importantly, France’s population was still growing. What changed? Farmers improved their craft, slowly increasing yields and also switching to more productive crops (France went from rye to potatoes). The result: more food for the same amount of land. France’s government also switched their policies. They went from incentivizing you to clear the land to having policies for deforestation and getting communities to use more productive farmland. And the big one: France swapped wood for coal for much of their energy needs.

This pattern of deforestation occurs in other countries as well:

“These changes meant that rich countries managed to decouple population–and economic–growth from deforestation. This trajectory is a consistent pattern that we still see across the world today. It follows a country’s journey from less to more industrialised. Deforestation and development are tightly linked when a country is poor, but this relationship eventually breaks down. Once countries get rich enough, forests stage their comeback.” (Chapter 4)

You might be thinking, “Switching wood for coal isn’t that great of a trade.” And I agree that going down the path of fossil fuels created new problems. But I think it also afforded many countries the initial economic growth that now gives us the chance to help everyone grow while limiting downsides such as air pollution.

Clean air is the second example of decoupling I want to highlight. Air pollution comes from burning items, such as wood or other biomass. The burning flings small particles in the air, which then get into our lungs and create all sorts of health problems. But it’s a tradeoff people have been making for hundreds of thousands of years:

“Whether or not they were aware of the health impacts of what they were breathing in, the sacrifices of giving up wood-burning were severe. They needed fuels for cooking, heating, light and safety. Perhaps early death from respiratory infections, cardiovascular disease or lung cancer was worth it for a better life. As we’ll see later, this is a trade-off that billions of people still face today. In the end, having a source of energy nearly always wins.” (Chapter 2)

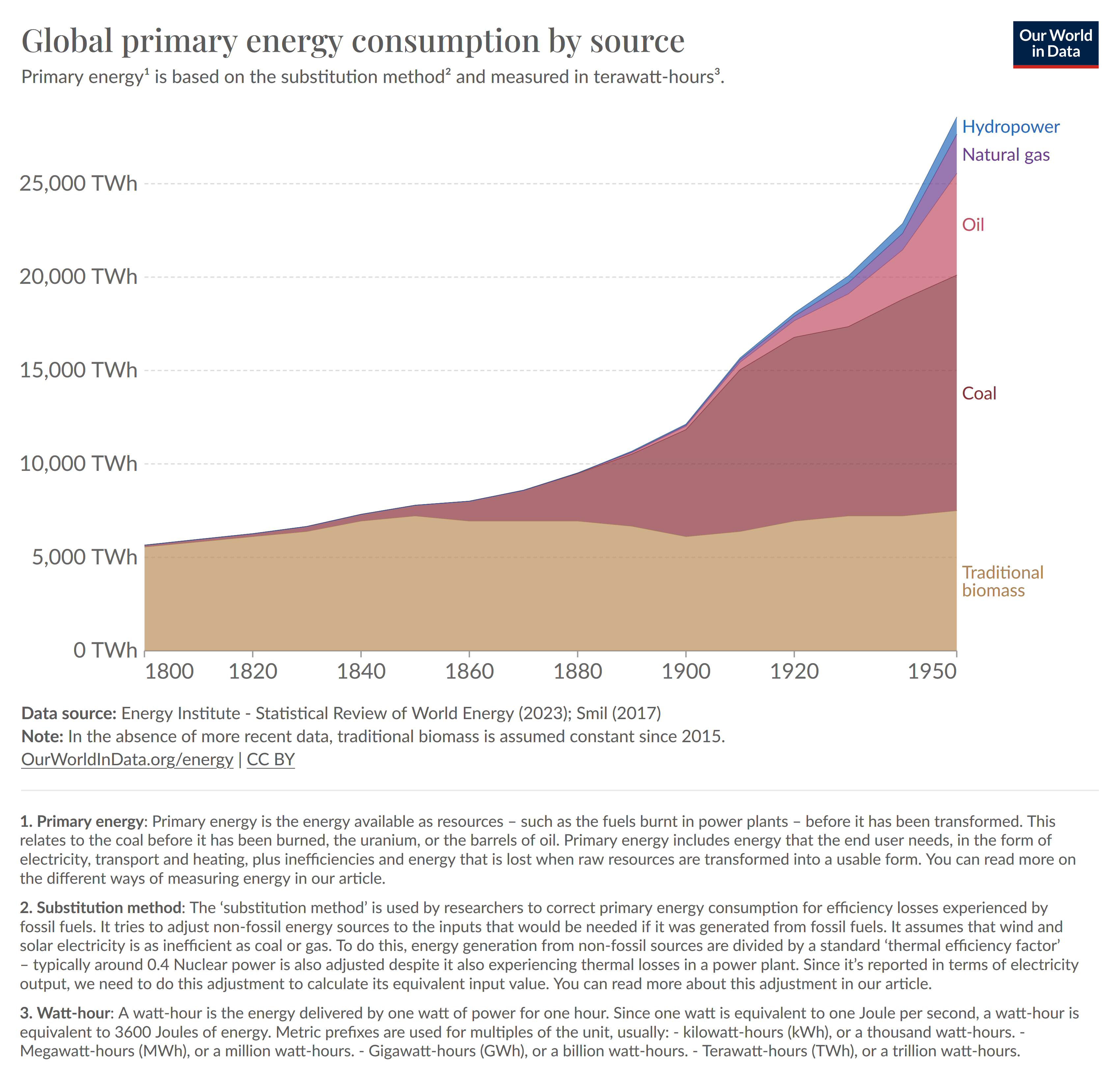

Once people discovered that coal yielded about double the energy compared to wood (per kilogram), they switched to it as a source for energy. You can see this in the following chart, where wood falls under traditional biomass:

Hannah writes about how the cities of Edinburgh and London exemplified the type of air pollution that burning coal creates. Smoke in homes from cooking, smog in the streets, terrible stenches, and particularly bad events such as the Great Smog of London which killed somewhere around 10,000 people made it clear that there were serious health consequences to burning coal. Hannah calls it a “silent killer, but one that seemed like an inevitable price to pay for progress.”

But today, London is so much better. Environmental regulation helped with this, banning leaded petrol and spurring companies to innovate and create technologies such as sulfur scrubbers for smokestacks on power plants and vehicles that emitted much less pollution.

The key isn’t to just ban everything and throttle the economy. Hannah writes that we don’t have to make the tradeoff between environmental action and economic growth. We can have both, and it’s the trend she sees in many countries worldwide:

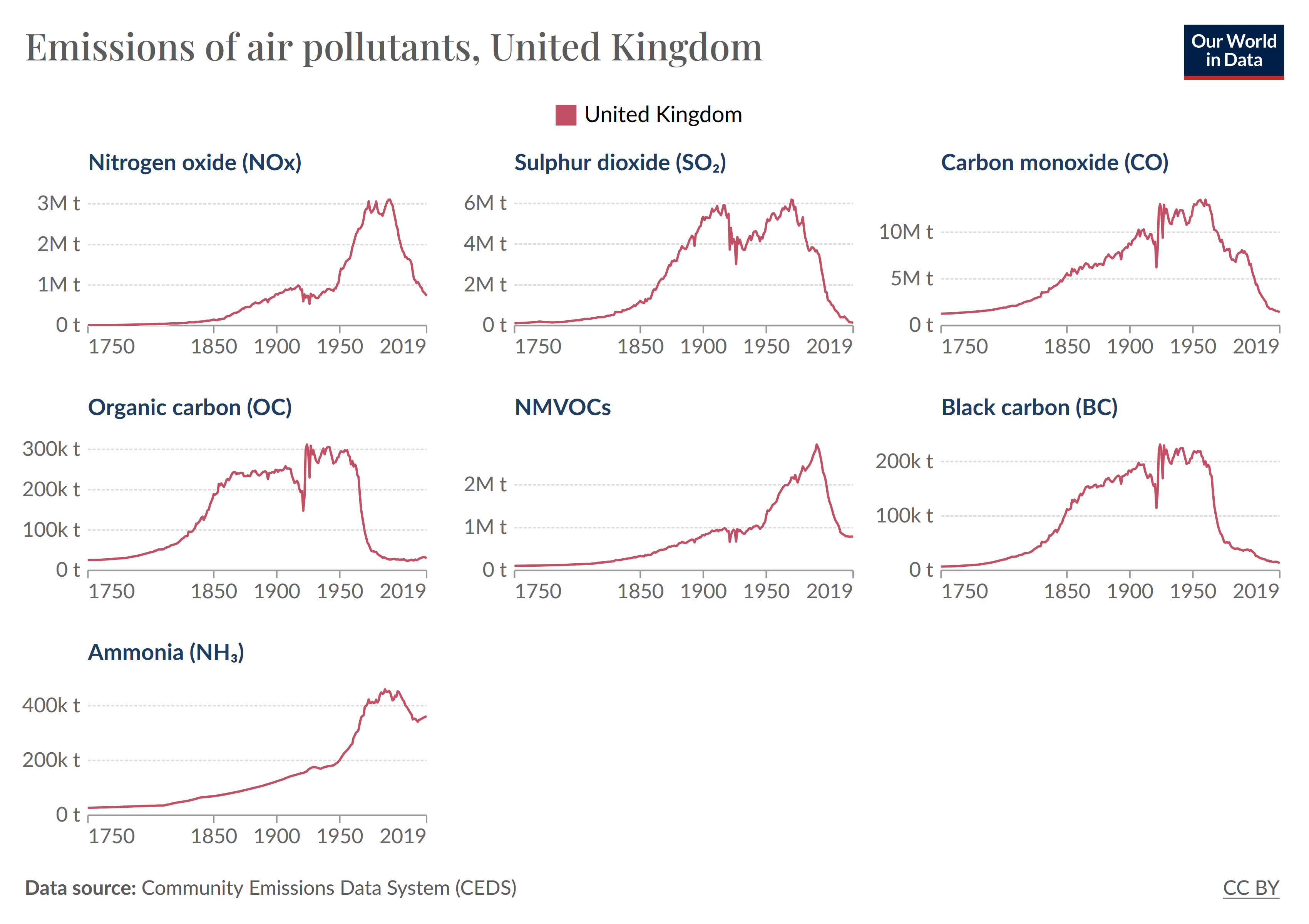

“The path that countries follow is a predictable one. Pollution first rises as a country starts to move out of poverty. At this stage, access to energy is the priority. It burns coal, oil, gas without tight restrictions on how clean it needs to be. There are no demands for top-of-the-range power plants with anti-pollution controls, or new car engines with particle filters. Pollution levels continue to rise as more people get electricity, cars, and can afford to heat or cool their homes. The country enters an industrial boom. People have more money and life is getting better. The pollution isn’t pleasant, but the trade-off seems worth it.

But, eventually, the country reaches a tipping point in its pathway to prosperity. Once life is comfortable, our concerns turn to the environment around us. Our priorities shift, and we no longer want to tolerate dirty air. Governments have to shift too; they are forced to take action and reduce levels of air pollution. The curve of air pollution reaches its peak and starts to decline.” (Chapter 2)

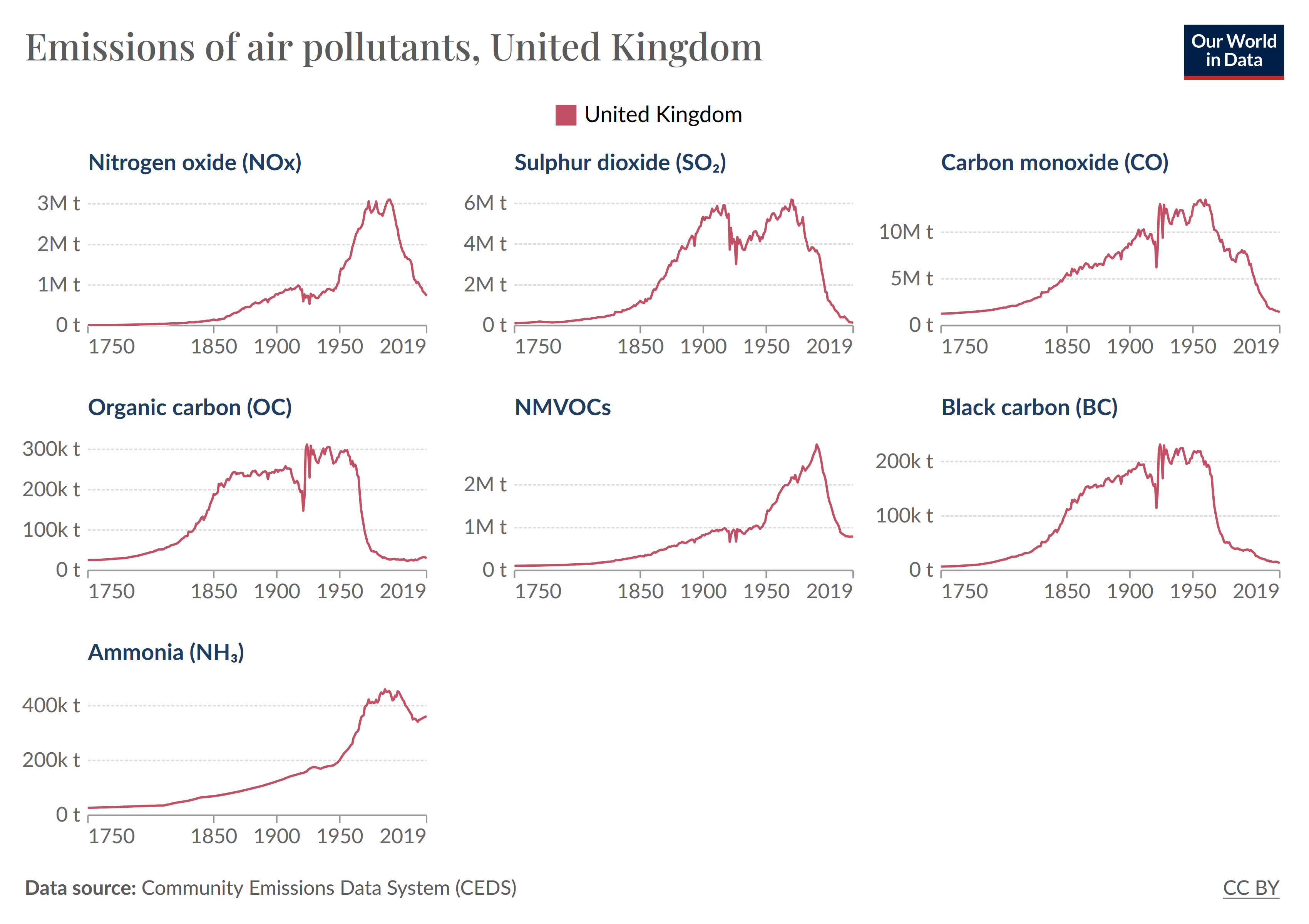

This phenomenon is called the “environmental Kuznets curve”, and though Hannah says it isn’t true for all environmental metrics (or other metrics), it does apply for air pollution. She makes the point that while it took a long time for some of the early countries to go through this curve (like the UK and the US), others are going much quicker because of technological advances:

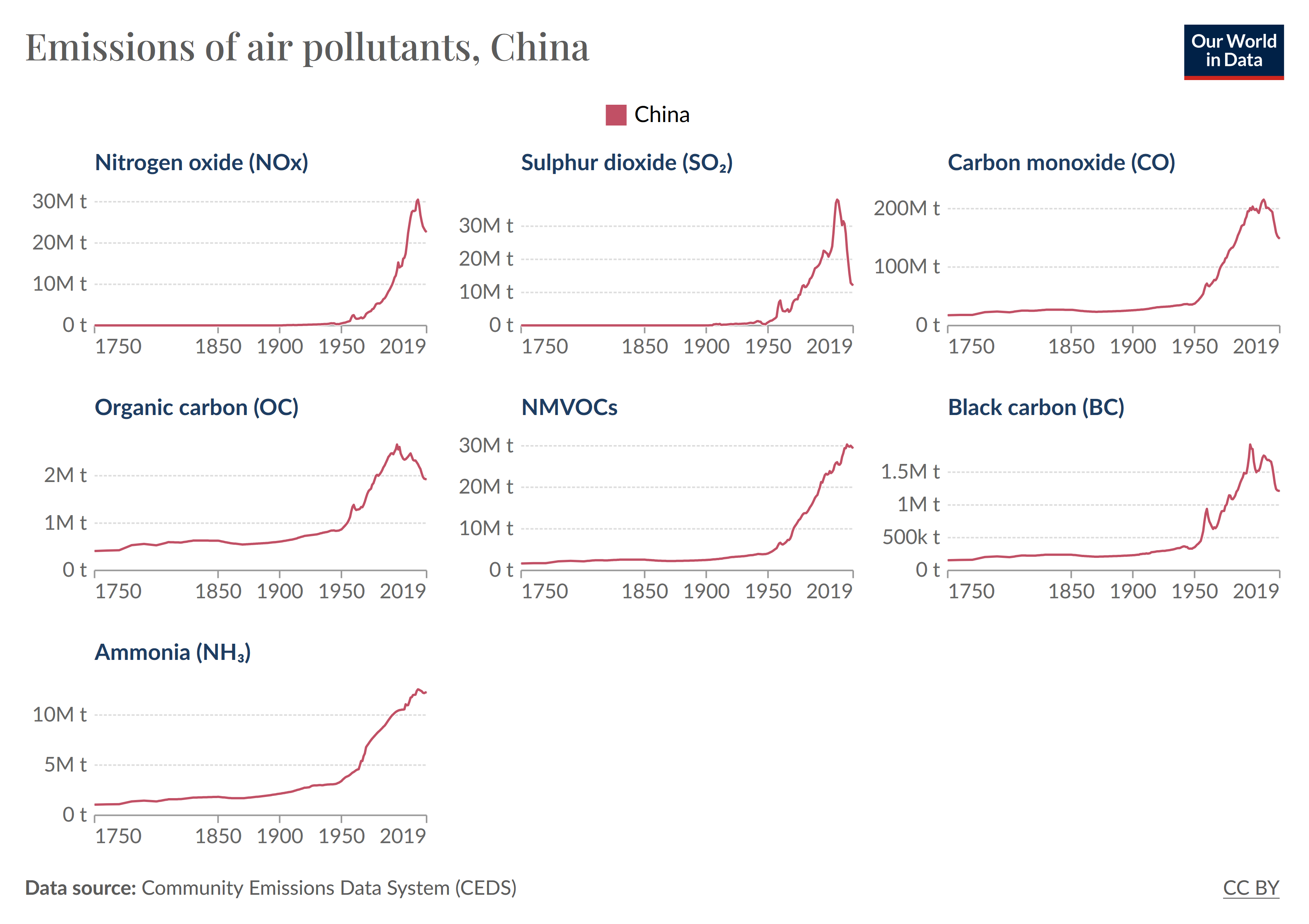

Compare this to a country like China (note the vertical scale is much larger because China has a bigger population):

Even better, these advances could help us get some countries through the curve without ever having to go through the “hump”. That would be a huge win, because currently about 4.2 million people die each year from outdoor air pollution, while 3.8 million die from indoor air pollution. Hannah compares this to the number of people who die from smoking (~8 million) and road accidents (~1.3 million). But getting across the curve is only possible because of the combination of environmental regulations and innovation as a response.

Depopulation and degrowth are not viable options

I appreciated that Hannah devoted some space to explain why depopulation and degrowth are not viable strategies for sustainability. The big idea is that our collective environmental impact is the sum of all our individual contributions, so we could either reduce the number of contributions (depopulation) or reduce the value of each impact through shrinking the economy (degrowth).

Hannah thinks both approaches are misguided, and I agree with her. When it comes to the population, we’ve already hit peak population growth4 (the rate at which our population grows each year). You can see this in the following chart:

The magenta curve shows the growth rate, while the turquoise-filled area shows the world population. If the population for a given year is P and the growth rate is G%, then the population the next year will be P(1+G/100). When the growth rate is positive, that means the population will be growing exponentially. But if you look at the projections from 2023, you see that the population is still growing, though more and more slowly. Once that growth rate goes negative around 2100, the population starts to decrease.

For our environmental impact, this means there won’t be an uncontrollable explosion in population. There are then some who want to go even further and deliberately lower the population (she quotes Paul R. Ehrlich’s roughly 1 billion figure from his book The Population Bomb). Hannah writes that any policy you wanted to implement globally to lower the population, this won’t happen nearly on the timescale we would need to make a dent in our environmental problems. The only way to get our numbers to “1, 2, or 3 billion people would mean killing billions or stopping people from having any children at all”. I don’t want to live in such a world. Do you?

To reign in our collective impact then, we will have to focus on slicing our individual impact. Hannah puts it well:

“The end goal that we’re aiming for is to reduce our impacts per person to zero–or at least very close to zero. If we’re to build a sustainable world for the future then we all have to tread with the lightest of footprints.” (Chapter 1)

If we can do that, population numbers will matter much less.

Hannah then tackles the degrowth mindset, which links economic growth with high environmental impact lifestyles (think: fossil fuels, extracting resources, using land, eating meat, etc.). In addition to decoupling economic growth from sustainability (as we saw in the previous section), she notes that global wealth isn’t even close to enough to put everyone on the $30/day poverty line of rich countries like Denmark. We’d have to make the global economy five times bigger to achieve this, which is what we’d want to do if we’re trying to satisfy the first pillar of sustainability. This fact was very surprising to me, and it made me see economic growth in a different light. As Hannah quips, “A world without any economic growth would remain a very poor one. A world with degrowth would be even worse.”

Overlap

Despite the book being an exploration of seven big problems, what I learned from reading is that they aren’t independent. Instead, they overlap. Making progress in one area often means making progress in several others. This isn’t to downplay the work ahead of us, but it does make our quest for sustainability a little easier.

For example, burning stuff is responsible for our air pollution. Burning less would be good for our lungs. But it would also help our efforts against climate change, since much of that stuff is fossil fuels like coal. Moving to cleaner energy sources would do good on multiple fronts.

This isn’t an isolated instance; it’s the pattern. Hannah has a section about eating meat, which is my favourite example of overlap from the book. Eating meat (beef in particular) is one of the most emissions-heavy foods we can eat. Shifting our diets by eating a bit less beef will reduce the number of cattle we have, which directly lowers methane emissions. But then there are the knock-on effects. Fewer cattle means we don’t have to feed as much of our food to them and can instead feed it to people (41% of the food we produce goes to livestock). We also won’t need as much farmland (currently occupying about half our usable land on Earth), so we can cut down fewer forests, which then limits biodiversity loss.

As usual, Hannah has a good perspective:

“The problems we’re facing are tightly interconnected. The worry is that this gives us impossible trade-offs; we’ll be forced to prioritise one problem at the expense of another. But it isn’t the case; instead, these interdependencies mean we can solve a lot in one go. Move to renewable or nuclear energy to improve air pollution and climate change; eat less beef to improve climate, deforestation, land use, biodiversity and water pollution. Improve crop yields to benefit the climate and humans.” (Conclusion)

Better, not perfect

The book’s subtitle is “How We Can Be the First Generation to Build a Sustainable Planet”, and Hannah delivers. For each problem, Hannah writes “How we got to now”, then follows it up with “Where we are today”, and finishes with paths we can take. This infuses each chapter with a mix of history and hope. Instead of ending each chapter with the feeling that we were screwed, I got the sense that we had a daunting challenge ahead of us that was solvable. As Seth Godin would say, these are problems, not situations.

I spoke to Hannah for an upcoming podcast episode of CarbonSessions, and she made a very good point about these paths: none of them are perfect. No matter what we do, there will always be tradeoffs. But that shouldn’t stop us from taking action and implementing better—yet imperfect—solutions. For example, eating meat is a huge burden on our yearly emissions budget (in addition to all of those other concerns I highlighted). It would be fantastic if all of us who have a rich variety of food would switch to plant-based diets. Yet the reality is that diet is a big part of our identity, and most of us won’t just completely change what we eat. What is much more realistic is finding tasty plant-based meals that could substitute a few of our lunches and dinners each week. And that can make a large difference: I learned that we can actually make huge gains just by shifting to a less beef-intensive diet, without cutting all meat completely. That’s a huge win when we are searching for ideas that whole populations could adopt.

Personally, I am not a vegetarian yet. But I have slowly started shifting my diet, and I’m at the point where roughly 50% of my meals are plant-based. Am I minimizing my emissions from my diet? No, but 50% is not nothing! Speaking with Hannah, it was clear to me that she is much more pragmatic about finding better solutions over perfect solutions.

My one counterargument is that we could get trapped in a local minima where we implement an imperfect solution that now blocks us from moving to an even better solution. The blocks I’m thinking of are more social and political in nature, but I think they could pose issues despite not being about technological or scientific breakthroughs.

Data is useless in isolation

If I tell you that one in ten people don’t get enough calories, what’s your reaction? Hopefully you agree this is a terrible fact of the world. How can we solve this problem? If you only have that statistic, then you might think, “We’re not growing enough food.” You might then focus your efforts on policy favouring more production from farmers. But then you might learn that we actually produce enough food to feed the world twice over (over 5000 calories a day per person, see Figure 1). The problem isn’t supply, but food loss, inequality, and feeding food to animals and machines. With this second piece of information, you’ll probably pursue very different strategies.

What Hannah’s book shows over and over again is that any particular data point is useless on its own. To make sense of any number, you need to understand the constellation of data around it. As Hannah told me in our conversation, you need the right context.

It’s even more relevant when thinking about these global problems. By definition, the numbers often aren’t going to be in the hundreds but in the thousands, millions, and billions. These are hard scales to relate to! The only example I can think of where many of us regularly interact with the lower end of these scales is money. But otherwise, these numbers are on alien scales, making them all seem “big”.

Yet a million and a billion are very different quantities, and they matter when it comes to talking about solutions. Hannah gave me the example of looking at CO2 emissions. If you see a statistic that some process unleashes tens of thousands of tons of CO2 per year, that looks bad. But when you put that number beside our 37.15 billion tons of CO2 emissions in 2022, it suddenly doesn’t seem so big.

If we want to tackle all of these problems, we cannot waste all our energy on solutions that give us small wins. We need to triage, and data helps inform us on where the biggest benefits may be. Data and science will never tell us what to do, but they can tell us where we stand to gain the most.

Throughout the book, Hannah’s message is simple: We aren’t screwed. In fact, we’re in a great position to become the first sustainable generation. Her book is one of hope, but also practicality. It’s not that we are simply going to cross our fingers and wish ourselves across the finish line. There are actions we need to take as people (such as shifting our diets), but also actions we need to take as countries (moving to cleaner energy, prioritizing air quality, protecting biodiversity, and more). Both need to happen, but especially the systematic changes on a national and global scale.

What I love the most about Hannah’s work is that it never shies away from the problems we’re up against, yet it also doesn’t settle for despair. Not the End of the World cuts through a lot of the overwhelm I feel when it comes to the environment. But it did more: the book reminded me that there’s plenty of tasks left to do, and each one will bring us closer to a sustainable world.

Thank you so much to Elle Griffin for feedback on this piece, as well as Hannah Ritchie for our conversation about her book and the context around it.

Endnotes

-

As she mentioned just last week, “While most journalists have only asked me climate questions about my forthcoming book, that is only one chapter of it… Climate is not the only problem! […] In fact, climate is not even the biggest problem for human wellbeing right now (although that could change). Air pollution kills millions every year.” ↩

-

Though not entirely. As Hannah writes in her chapter on conservation, with a population of only up to 5 million people (~1/2000 the number now), humans hunted hundreds of large mammals to extinction. There’s a lot we were able to do with small numbers. ↩

-

My friend Malcolm Cochran has a nice essay about deforestation and automobiles in New England. ↩

-

I would note though that just because we’ve hit a peak in population growth, we aren’t destined to never go higher again. ↩