The Journey to Completion

As a scientist, the usual “proof of work” is the paper, a small artifact that encapsulates the essence of a problem and its resolution (or at least, progress the scientist makes). But the process of going from an initial idea to a finished paper is less clear for outsiders.

My goal here is to shed some light on the topic of projects, and all the work that goes into a paper. This is similar in spirit to how writers have gaps in between books in a series. Between publications dates, they need to plan, write, and edit their next book! It’s a lot of work, and makes for the long period between when a writer begins working on a book and when it goes out on shelves.

There are several stages to projects, and the time spent on each stage varies from project to project. Predicting these times isn’t the goal of this essay. Instead, I want to give future graduate students an idea of my own experience in completing a research project.

First, there’s the initial idea. It comes from a variety of places, including your supervisor, a paper you’ve read, discussions with others, or even just a burst of inspiration. At this stage, you start to poke at it, testing its boundaries.

This tends to be one of the most exciting times, because you’re still in big-picture mode, imagining how this will change the world. I’m often wrong about this, but your experience may vary.

Second, there’s the exploration. If you’re working on a mathematical result, this could mean scouring the literature for papers about this topic to see if there’s a place you can add insight. If you do experiments, my guess (not being an experimentalist myself) is that you start looking if measuring this change or quantity is even feasible. If you’re like myself and work in theory, then you might try some initial numerical simulations or play with the equations of your system.

In this stage, you will discover more about your idea. In fact, this is how you know if the initial idea is any good. Sometimes, nothing comes of it, and it dies at the exploration stage. In other cases, exploring triggers new ideas, and maybe even brings along a few surprises.

Exploring takes time. In my case, this often means writing code to test hypotheses I have before moving on to working with mathematics. I like the rapid prototyping of building a small numerical experiment and seeing if what I’m thinking even works. If it does, I’m encouraged to keep digging.

Dead ends often occur here. That’s because you’re exploring. The key is to not get frustrated by things not working out. That’s research, and it’s often confusing. I liken it to stumbling around in the dark with only a flashlight that emits a very thin beam. Sometimes you’re lucky and make progress right off, but often you’re forced to stumble in a few directions before anything looks promising.

I’ll repeat: Failure is normal here. Don’t give up! Use your knowledge of your idea to gauge if you should keep on exploring. If it was a wacky idea, then maybe you give up on it quickly. But if the idea makes sense from multiple viewpoints, you may work on it for longer.

During the exploration stage, you will notice things. Perhaps that numerical experiment didn’t pan out, or this one found something strange you can’t explain. Maybe you found an earlier result in the literature that has some relevance to what you’re doing, though you don’t quite understand it. I collect all of these, because they will be what I use to judge if I choose to continue to the next stage.

The third stage is refinement. If you succeeded in finding several useful bits of information, then you want to take these further. To give the example of numerical experiments, you might want to scale up to larger system sizes to demonstrate a result in the thermodynamic limit. Maybe you want more samples so your results are more robust. Maybe you found out how to extend a minor result in another paper, and have hope that this can translate into a major result.

The purpose of this stage is to take the information you collected while exploring and refining it. This is what takes you from the realm of a few different scattered results to a publication.

A key consideration here is the story you want to tell. Since you’re getting closer to turning these results into a finished project, knowing your story is important. I wrote about this last month, and the important part is to know how to pitch your story to an audience. This will shape which bits of information you emphasize, and what you refine.

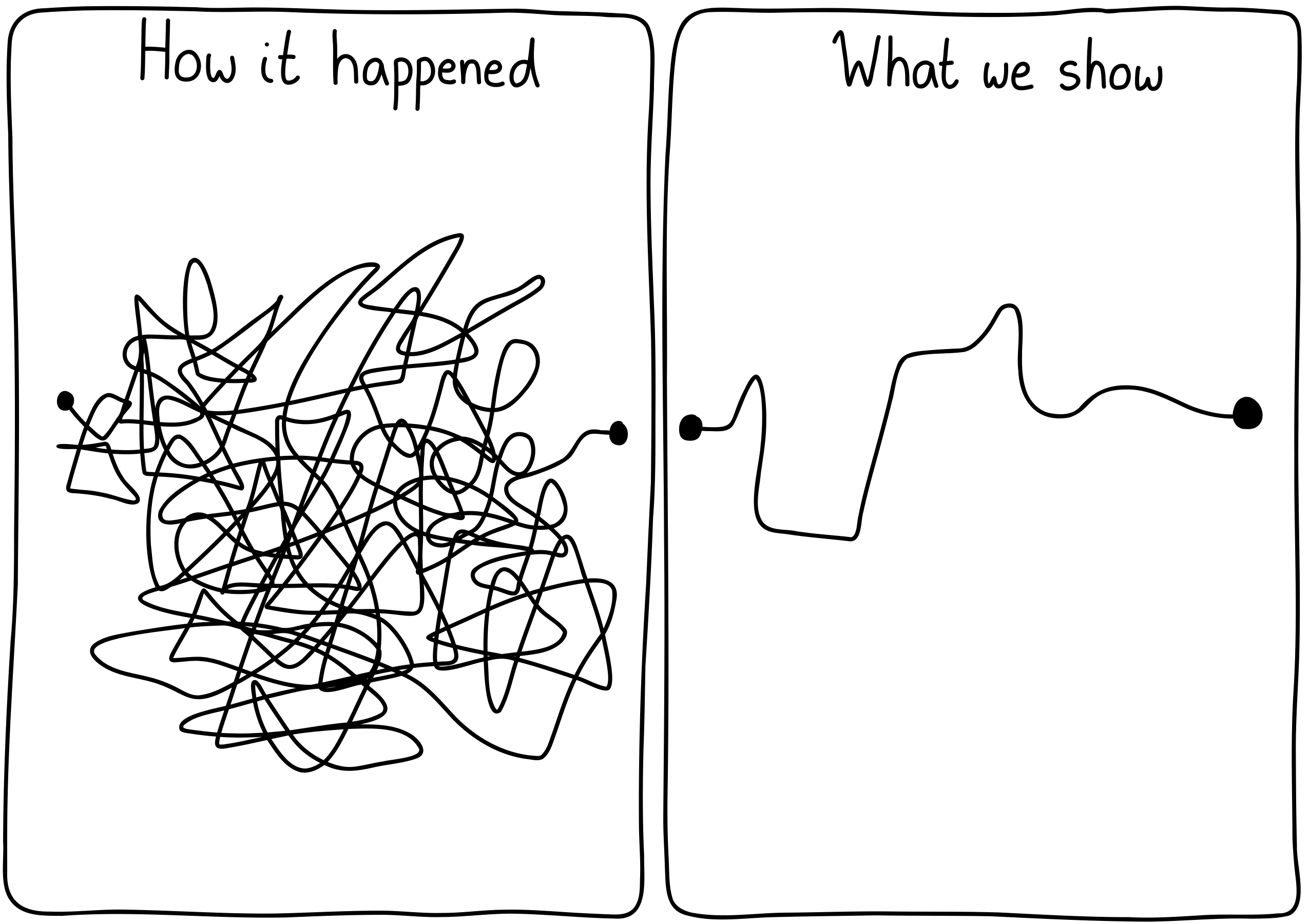

One caveat is that you often don’t go through these stages linearly. You will often hop back and forth between them, as you find out more about your project. This is makes a project take much longer than you would think. Maybe a result you were refining didn’t work out, so you have to try another path. Maybe your numerical results aren’t as strong as you hoped, so you have to rethink your approach. These things happen, and it’s why you need to be resilient as you continue your project.

In my own experience, this can be the low point of a project. You thought you had exciting results, but now that you have to polish them as much as possible, they don’t appear as nice. I’d say this is a normal feeling, and it’s good to keep in mind the overarching purpose of the project during this time. Not only will it help you craft your story, but it will reinvigorate your work.

The fourth and final stage is writing. This also includes revising, and it’s what you do once you have a story, some results, and are confident that they are important enough to warrant publication. This might be the last stage, but it’s also the trickiest if your goal is to truly serve your reader.

At this stage, there’s no hiding from unclear concepts. If your work relies on something you don’t understand well, it will come up again and again as a point of confusion. That means you want to understand all aspects of your project (or if you’re working with many people in a collaboration, there is always someone who understands each piece). In my own experience, this means I have to refine my results even more, to the point that I am confident I can answer most questions about them.

As you write, you will notice places where your understanding isn’t clear. Writing (and rewriting!) clarifies this. And yes, even for someone like myself who loves to write, this can be a painful stage. You will look at the same words and ideas over and over again, until they are seared in your brain. So make sure you take frequent breaks to make this rigorous process bearable.

At some point, you will declare victory on the manuscript, which will not only be polished, but every result within is polished as well. A finished manuscript doesn’t just mean you found the right words, it means you found the right story, the best way to present the data or results, and connected it back to other ideas your audience knows.

This all takes work, much more than I expected when I wrote the first draft of my first PhD project. The “fun” part of being a scientist may be the exploration stage, but as professionals, we need to turn those explorations into pieces of knowledge.

The journey is nonlinear, confusing, and prone to restarts.

Endnotes