Each winter, I set a goal of not slipping on ice during my runs. Each winter, I’ve failed. Bruised hips and scraped knees tell those tales. Darkness is the primary factor. A typical run begins long before there’s even a hint of morning light. My steps are never fully confident, the snow concealing potential danger on the road.

Step here, step there.

Keep my feet light.

Slow down before turning.

Watch out for snow-filled potholes.

It’s part muscle memory, part good intuition, part reflexes, and part guessing game. A small relief: On my most frequent road for dark winter running, the 9 lampposts emit bubbles of illumination. They reassure my steps, if only briefly. But near the end of the cul-de-sac lies a stretch where there are no more bubbles and it’s just me with the darkness.

This year I have hope though: My town installed an extra lamppost, providing one last bubble of light. Perhaps this year will be the year I succeed.

Either way, I soon won’t even notice the lamppost as being “new”. In a few years, I may not even remember that there was a time without its light. But it will make me safer.

That’s the nature of infrastructure: when operational, it’s an invisible supporting actor in our lives. It’s unassuming, quietly working in the background to enable everything else in my life. Imagine if I had to manually turn on my lampposts, or send a request to my town to activate these particular lights at a certain time! It’s absurd, which is why infrastructure functions best when it’s invisible.

In fact, it’s when things go very wrong—a natural disaster, a human accident, or a tipping point in a system—that we sadly remember. Infrastructure failures expose the concealed wiring of our civilization.

Such an event happened in Québec (and eastern Ontario) in 1998. Its scale was so massive that my older family members still reference it. Overnight from January 4th to 5th, freezing rain poured down on the province. This isn’t so unusual. But the freezing rain didn’t stop. Instead, it kept coming. And coming. And coming. It went on for six more days, at which point some areas had received up to 100mm of freezing rain. In comparison, Canada’s previous largest ice storm pelted down only 30-40mm of freezing rain.

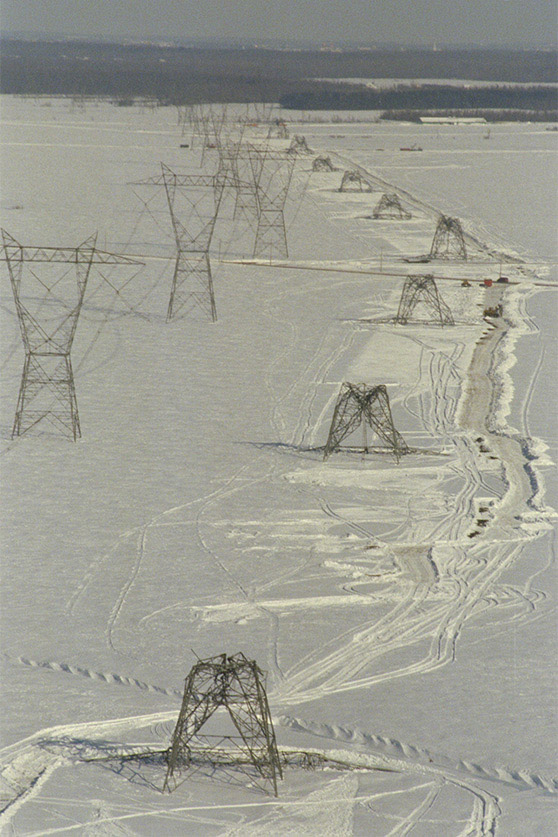

To give you a glimpse of the scale of the problem, take a look at this photograph during that time (from Hydro-Québec):

These storms don’t just make roads and sidewalks slippery. Freezing rain clings to surfaces, weighing them down. The rain transformed trees and transmission towers into ice sculptures whose structures suddenly had to bear quite a bit more weight. Trees snapped, their branches snagging on power lines. Over 1000 transmission towers fell, many buckling over their own weight, knocking out the electric grid.

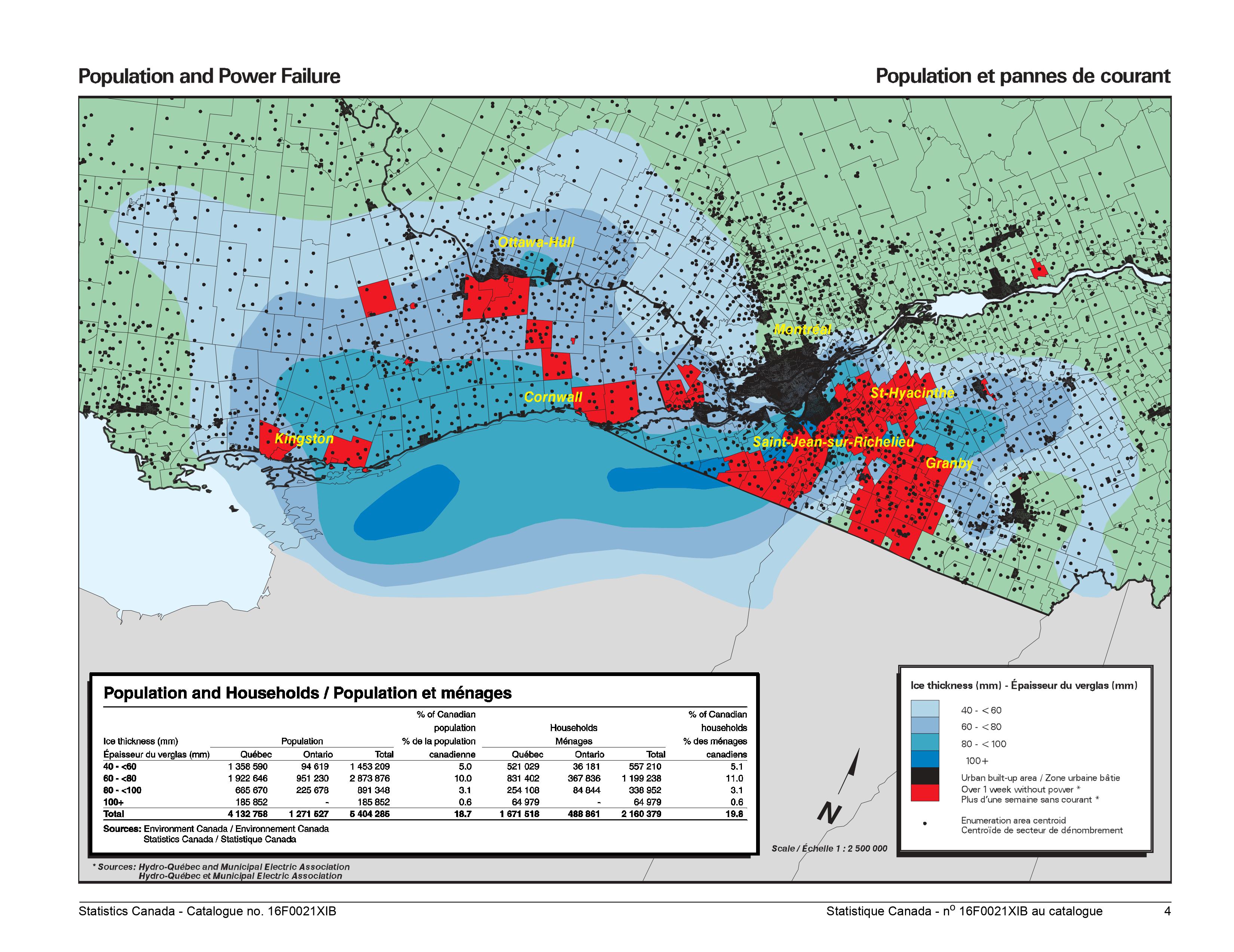

Hydro-Québec, my province’s main electricity provider (along with other organizations), began repairing the broken power lines and electrifying the province again. But this took time. Millions of Québecers had no electricity for days and over a hundred thousand had none several weeks later (p. A3 of the January 28, 1998 issue of Globe and Mail). The winter is a bad time for the electricity to go out when around ⅔ of the households use it for primary heating. Several people died from hypothermia or from carbon monoxide poisoning through burning dangerous fuels indoors (p. 17). As you can see in the chart below from Statistics Canada, the extent of the storm was vast and many regions were out of power for more than a week.

Our electric grid had several flaws which turned an extreme event into a disaster: the transmission lines could only withstand about 45mm of ice (many regions received that as a minimum), one falling transmission tower could unleash a domino effect on many more, and overgrown vegetation meant snapping trees could damage the power lines.

Failing infrastructure can be so devastating because we take it for granted. Like thinking you’re at the bottom of the stairs when you still have one step remaining, we’re left flailing when infrastructure breaks because we completely depend on it.

It’s also easy to forget that we built every single piece of infrastructure we have. It wasn’t always there. The problem is that we’ve inherited a lot of it from the past. It usually blends so well in the background that we treat infrastructure like the laws of physics rather than systems we can build, sculpt, and change. A lot of it was there before we were even born! But there was a time before smartphones and the internet, a time before weather forecasts, a time before highways, a time before traffic lights, a time before air conditioners, a time before cars, a time before electricity, a time before democracy and judicial systems, and even a time before modern waste management and toilets.

Each advancement required ingenuity, human coordination, and effort. They didn’t happen by accident, and the underlying problems were thorny (and still are in some regions). When we only think about infrastructure during times of crises or failures, I fear we forget how vital it is to our lives. Infrastructure is boring and invisible when it’s successful, and that’s kind of the point.

Yet I don’t want us to forget about infrastructure. I want us—those who benefit from so much of it—to learn how it shapes our lives. Doing so will remind us of two lessons. First, we’ve made progress on big problems before. Just consider our multi-century effort to electrify our homes, buildings, and streets. We turned a problem of energy access into the electric grid we have today. That should strengthen our confidence that we can make progress on our current challenges (and for more people). Second, infrastructure creates new problems. If we want to be capable of fixing them, we need to notice infrastructure and understand how it works.

In the case of the 1998 ice storm, Hydro-Québec learned from its mistakes and rebuilt a more robust and resilient electrical grid that will do better if a similar storm appears. Success will mean we don’t notice. But we should. The first step to improving and building new infrastructure is to notice its presence and to appreciate all that it enables (both the good and the bad!).

Infrastructure isn’t just about technology, either. As Paul Edwards writes in his essay “Infrastructure and Modernity: Force, Time, and Social Organization in the History of Sociotechnical Systems”:

Power outages or traffic jams cause most of us to think of downed power lines or inadequate roads, rather than to question our society’s construction around and dependency on them.

If technologies are the “atoms” of infrastructure, then social organization is the glue that holds them together. Infrastructure is social and technological. Edwards points this out right in his title: infrastructure is sociotechnical, and you can’t pry them apart. This suggests that understanding infrastructure requires going further than learning about technological progress. It also requires understanding institutions and social organization.

When millions had no power during the 1998 ice storm, Canada launched Operation Recuperation, deploying over 15 000 members from the Canadian Forces (more than any other instance within the country in history). The troops were crucial to the relief effort, yet they weren’t infrastructure in the form of technology. Rather, they were an institution that Canada could call upon when disaster struck. In this sense, I consider them just as much part of infrastructure as the electric grid that Hydro-Québec rebuilt. They both enabled the storm to recede into history and the back of our minds.

Here’s a list of questions I don’t worry about: Where will I get my food? Do I have clean fuel to cook? Can I store food for later in a refrigerator or freezer? Where can I get clean water? Will my shower serve me hot water? Can I read at night with an electric light? How can I talk to my faraway friends who I haven’t seen in years? Infrastructure is a big part of why I don’t worry about these questions.

Right now, it’s a privilege to not have to worry. But I want to turn this into a basic fact of life for everyone. I think part of the solution is building literacy in infrastructure, so that those like me, who’ve often taken infrastructure for granted, can appreciate just how far we’ve come, then identify the issues with our infrastructure and give us the confidence to go even further. Our world still has many problems left to turn into infrastructure.

A big question I do worry about is: How can we decarbonize our civilization while still growing and creating opportunities for everyone to flourish? It’s an immense challenge, one that can seem paralyzing amidst the flood of dismaying news about our climate. But I think by learning about infrastructure and appreciating its history, we can inspire people to make progress on these current problems, just like we did in the past.

Progress transforms problems into invisible infrastructure, and my hope is that there will be a future generation where this question has faded into the background of their lives.

Note: Parts of Paul N. Edwards’s great essay “Force, Time, and Social Organization in History of Sociotechnical Systems” and an article entitled “Invisible infrastructure is the background to our modern lives” by Sarah Bell, Charlotte Johnson, Kat Austen, Gemma Moore, and Tse-Hui Teh inspired this piece.

Thank you so much Elle Griffin, Tina Marsh Dalton, Rob Tracinski, Anthony D’Apolito III, Becky Isjwara, Harrison Moore, Paige Lambermont, and Anna Mackenzie for feedback on this draft.