A Simple Puzzle

I love simple puzzles with elegant solutions that are perhaps unexpected. I particularly enjoy it when these puzzles can be solved without invoking a whole bunch of machinery to support the solution. Mathematical machinery is nice, but a great simple puzzle can be a great segway into that machinery. As such, invoking it right off the bat kind of misses the point.

For this post, here’s the puzzle I’m thinking about:

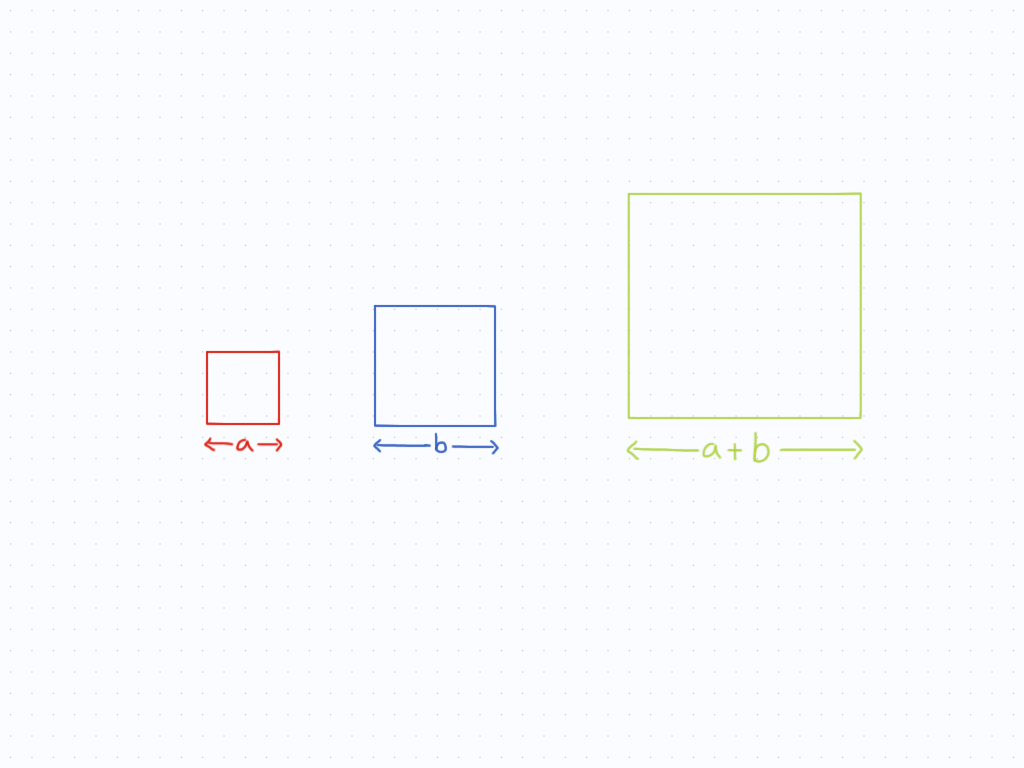

Can you find two squares of lengths $a$ and $b$ which have an area equal to a square of length $(a+b)$?

If you prefer a diagram version of this problem, here it is.

At first, this puzzle seems simple enough. How hard can it be to match these conditions? But after a few attempts, you may start to get frustrated, because they don’t seem to work. It’s as if the question is deliberately trying to work against you, thwarting each attempt. The right combination just doesn’t seem to be there. What’s up?

After a while, you may start to think that the answer to this puzzle, is no, it cannot be done. To show this, you might start to wonder what the area of the two squares is, and what the area of the larger square is. Then, by comparing them, we can see if there’s some way to make them equal (or to show that they aren’t).

The total area of the smaller squares is simple. Each square has an area of $s^2$, so the total area is $a^2 + b^2$. For the larger square, the side length is $(a+b)$, so the area is $(a+b)^2$. But what is this result when you square it? Expanding the term simply gives $a^2 + 2ab + b^2$. This is awfully close to $a^2 + b^2$. In fact, the two expressions would match up if that pesky $2ab$ term wasn’t present. To do this, we would need $2ab=0$. But this implies that either $a=0$, or $b=0$ (or both). And that can’t happen in our situation, since we’re trying to find squares with the given property. Additionally, having a square of side length zero seems like we’re cheating, so we ignore that situation. Therefore, the answer is that we can’t find two squares of side lengths $a$ and $b$ which have a combined area equal to a square of side length $(a+b)$.

This is a nice result, because it turned a geometry problem (find the areas of squares) into an algebra problem. Most students will know how to expand $(a+b)^2$, but I’m guessing the geometrical connection might not seem so obvious. This puzzle teases out this precise notion. In fact, what it tells us is that we need to add a “correction factor” in order to make the equality hold. In this case, the correction factor is $2ab$, which we could also give a certain geometrical meaning.

I think that these kinds of puzzles are really what mathematics is about, fundamentally. It’s about these unexpected, surprising connections that can link different topics within mathematics to give answers to questions. I also find it challenges students to think about questions in different ways that aren’t necessarily obvious, which is a good skill to have.