Going to the Extreme

Last summer, the site Brilliant ran a program where participants tried to answer one new problem every day, within varying topics and of different difficulty. One in particular was interesting. Unfortunately, I can’t seem to find it on the site, but this is roughly how it goes:

Imagine you are on a boat in the middle of a lake, and there is a stone on board. You pick up the stone, and then toss it into the lake, where it sinks to the bottom (which means the density of the rock is greater than the density of water). What happens to the lake and the ship?

On the site, the question isn’t open-ended, but instead is one of four possible answers. These include things such as: the boat rises, the water level rises, or either of the two sink. Here though, I want to discuss the answer, and how one comes about it. In particular, I want to talk about how taking an extreme perspective can help one come up with the correct answer, no fancy physics involved.

I remember when I first read the problem, I asked myself, “Well’s what’s the radius of the rock? How massive is it? What kind of shape does it have?”

These are all questions that I thought were needed to address the problem, but it turns out that they aren’t. If you want to try your hand at answering the question, now is the time to do so.

To answer the question, let me give you a clear example that I think will make the answer more or less obvious in general. Imagine that you have a rock that is about the size of a pebble, yet has the same mass as a car. If that pebble is on your boat, what happens?

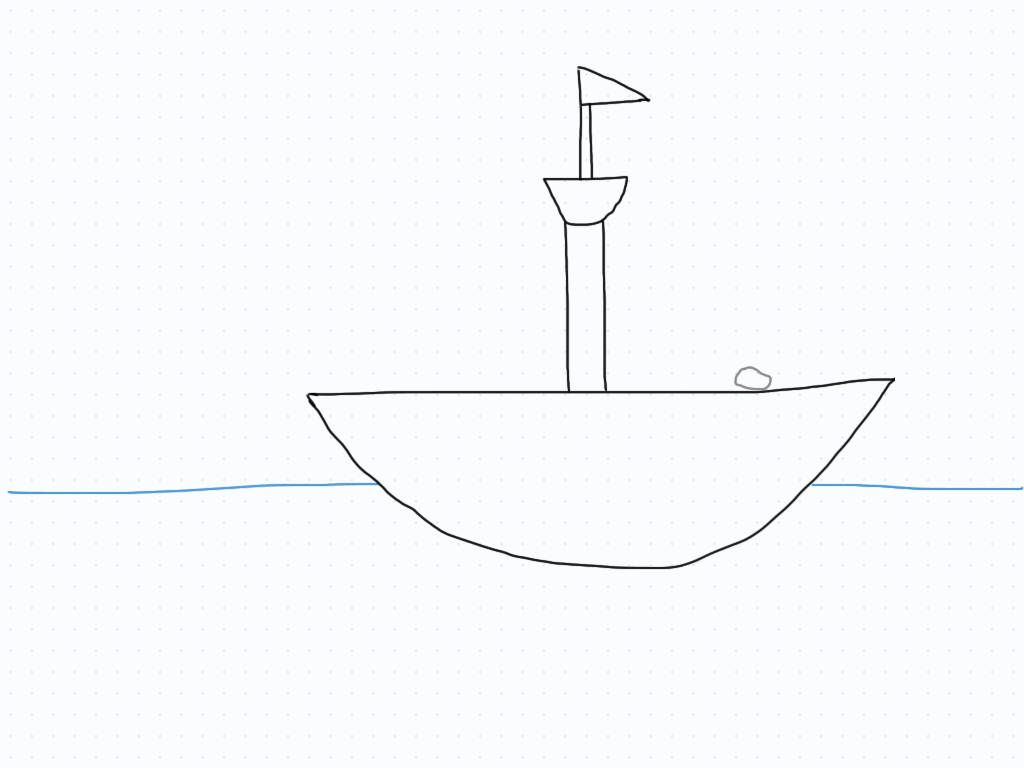

Evidently, your boat should pushed downward, before the buoyant force counteracts the force of gravity. At this point, the boat will be lower than without the pebble, so that water level in the lake should increase, since the boat displaces the amount of water equal to the submerged part of the ship. You end up getting the following situation.

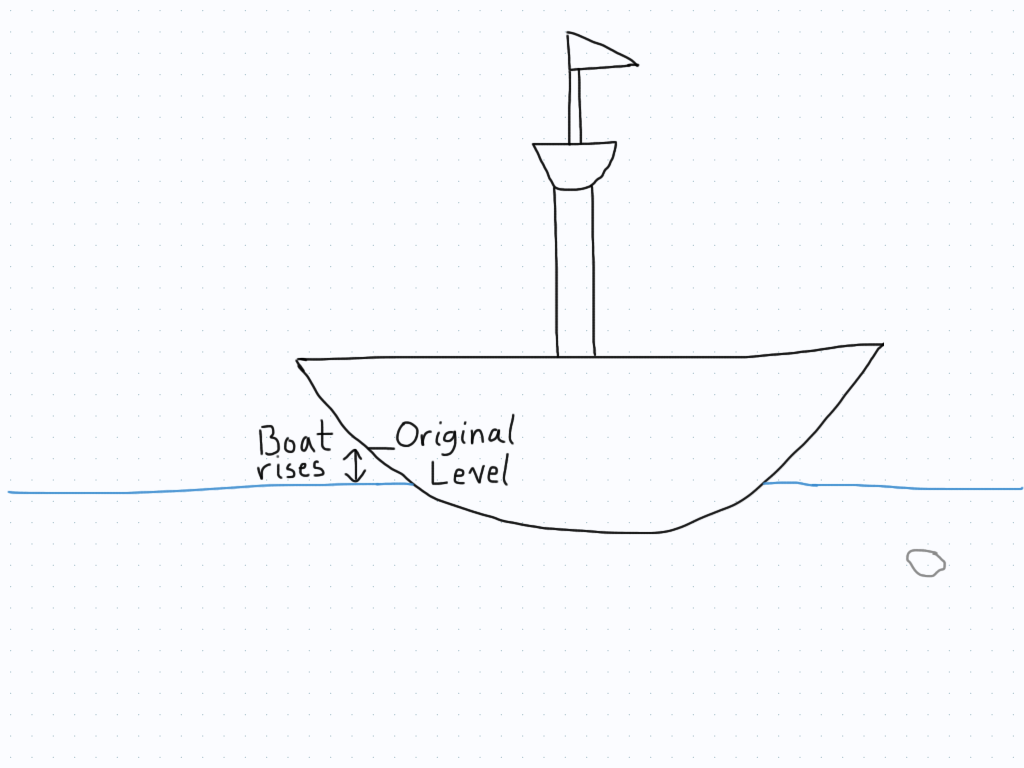

This is the situation that the problem begins with. The pebble is on your boat. Then, you find some inner strength and toss that pebble over the ship. What happens now? Well, the boat suddenly has a lot less weight forcing it down, which means the boat will rise. This happens because the buoyant force is now greater than the gravitational force at the moment the pebble is thrown overboard, which means the boat should have a net upwards acceleration.

At the same time, what happens to the water level in the lake? Well, remember that the water level was originally high since the volume of the submerged part of the boat was taking up place. However, with the boat floating upwards due to the removal of the pebble, the result is that less of the boat is submerged. This means less water gets displaced, and so the water level should go down. We can’t forget the pebble though. It has a certain volume too, which will increase the water level of the lake. However, the volume of the pebble is certainly less than the change in the volume of the submerged part of the boat, so the net result is the water level falling. As long as the rock doesn’t contribute to a larger volume change than the submerged part of the boat, this will be the end result. The boat will rise, and the water level will descend.

So there you go! By looking at an extreme example (a rock with a small volume, but a very large mass), the answer made itself clear. Instead of working with intermediate cases where the rock is sort of large and sort of massive, we examine the extreme cases (here, in opposite directions from what we would expect), and the answer is more apparent. The way I think about the above puzzle is in the following way. The rock’s mass on the boat translates to having the boat sink lower. This means the boat’s submerged volume will increase, and that increase in volume tends to be more than the volume of the rock itself, so throwing the rock into the lake means that less water is displaced overall. In a sense, the mass of the rock on the boat “contributes” to the displacement of the water more than simply its volume would.

Like I said, I love these kinds of problems because they showcase the power of thinking in the extremes. As one does more and more theoretical work in the sciences and mathematics, answers to questions usually come through using specific equations and some sort of mathematical argument. While that can be done here, I like the simplicity of the answer as well. It shows how one can answer questions in different manners and still arrive at the same answer. Yes, the quantitative analysis may be more precise and encompassing of the situation, but this skill of teasing out the extreme scenarios can also prove to be fruitful.