Black Boxes

Why is the area of a circle given by πr2?

I’m not asking why it’s in this specific form. Rather, I want to know why this is true. Can you tell me? Can you convince me?

Let’s take something a bit more concrete. I bet you use a lamp every day to light up something in your home. Can you explain how the lamp works? What makes the bulb shine? How does the electricity work to create this light?

These are all questions that have answers.

You know they have answers. I’m not asking technical questions here. Just a simple explanation for how the lamp works would please me. You don’t have to start talking about the various particles that make up the lamp, or how light behaves as a wave and interacts with the environment such that we are able to see.

Still nothing?

I’m not surprised. To be honest, I can’t even give answers to some of these simple questions.

You might think that we should be able to answer these types of questions. After all, we do use these things every single day. We should know how they work, right? And yet, most of us don’t know the inner workings of these machines and processes. We just know that they work, and that’s enough for us.

There’s a technical term for this in science (computer science in particular): a black box. This expression refers to a process or a device which we can give an input and get an output, but the inside of the black box remains unknown. The only feedback we get is the output.

This is not something we want in science. We would much rather have a process in which we knew each step along the way and how it went from step to step. However, in the absence of anything else, a black box that gives results is still useful. We aren’t going to throw away something that works just because we don’t know much about it! Black boxes signal that we have more to learn about (starting with the inside of the black box).

We all carry around our own black boxes. These are processes that we know happen around us, yet we don’t have a clue what the inner workings are like. From our cars to our refrigerators to the internet, most of us don’t actually have any idea how these things work. We might be able to jumble along together an ad-hoc explanation, but these tend to be wrong and not thought out at all.

When reflecting on this though, we often don’t care that we carry around these black boxes. It’s unreasonable to expect us to be knowledgeable about everything we use, so who cares if we don’t know how our car works? We know how to drive it, and that’s all that matters.

To a certain degree, that’s true. Often, we are able to get by with only the knowledge of how to use our black box. We don’t need to know how it works. As long as we steer the car and follow the signs on the road, we trust that the car will do its thing and not malfunction.

The issue is more about our perception of these black boxes. How many black boxes do you think you have? Chances are, the number you gave is too small. Way too small. The simple truth is that we use black boxes throughout all of our lives, often without realizing it. This is of particular interest when we consider education.

Black boxes everywhere

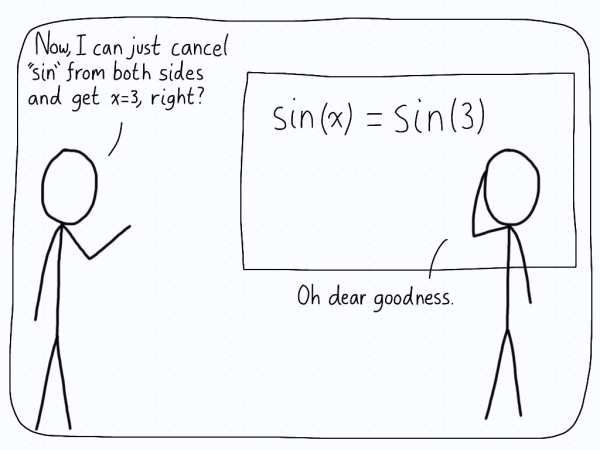

So we are in agreement that people do use black boxes in their lives. As such, it shouldn’t be a surprise that students use black boxes in their education. These are of particular use in subjects such as science and mathematics, where one can get many answers without knowing the underlying concepts. What seems like learning is just a focus on the outputs.

The danger with black boxes in education is that they are seductive. They represent a way to gather a lot of “surface-level” knowledge without digging deep to think about the concepts themselves. This means that if a student is having difficulty, it’s much easier to learn how to use a black box than to go through the longer process of absorbing the content.

I see this quite often in my field of physics. Physics uses a lot of mathematics, but it’s not as concerned about the mathematical concepts. This means that a lot of the tools of mathematics are transported to physics, and can be used without knowing the theory beneath.

Physicists encounter a lot of differential equations. However, professors teaching physics don’t often care about how one solves the equations. Instead, there are the staple differential equations, such as the simple harmonic oscillator, which every physics student knows and memorizes before they are done their education. Can they all explain the process of finding this solution (apart from telling someone to “plug it in and see”)? Probably not.

Here’s another example, this one not only about physics. If you take the function xn, what is the derivative? Any student who has taken a first course in calculus will tell me that it’s nxn-1. This is correct. But can the student then go on to explain why this is true? Perhaps the student who is in their first calculus class can (because they are in the midst of working with the definition), but I bet that many others who have taken many calculus courses and have long-memorized the power rule cannot. Instead, they might say something like, “That’s just how it is.”

Why does this happen? Why do we go from deep, underlying knowledge to trading it in for a black box that produces the right answer each time? The reason, I suspect, is because it’s much easier to remember the power rule than working it out from first principles each time. In fact, no one does that, because it’s a waste of time. Once we know the rules of the game, there’s no need to go back and rederive everything.

The issue occurs when we go for so long without looking at the first principles argument and only remember the rules themselves. This is what we want to avoid. It’s at this point that our knowledge goes from deep understanding to being a black box. We then cease to be knowledgeable about the subject. Instead, we become proficient at using the tools from the subject.

There’s a difference here, and it’s one that isn’t highlighted enough in school. Knowing how to use the tools of a subject to solve problems is a skill, but it’s not the same as understanding how those tools were developed. This is critical, because it informs how we make decisions about what to teach students. Do we want to focus on giving them skills to solve problems, or do we want to emphasize the concepts beneath? I don’t think we should focus only on one, but we are deluding ourselves if we think that schools (particularly early on) are emphasizing the importance of deep understanding. From my perspective, the priority is skill first, deeper understanding second. This aligns precisely with the use of a black box.

Students aren’t incentivized to dig deeper and develop more of an understanding of their subject. They’re incentivized to solve problems quickly and know how to do a lot of things. The byproduct of this is that black boxes are used to keep up.

Again, I’m not saying that the black boxes aren’t useful. They are, but if we want to do more than pay lip-service to the idea that students should have a deep understanding of their subject, we need to highlight this tendency to default to black boxes. On the other hand, if our priority is to only develop the skills of students, then fine, we can keep on using black boxes. We just can’t have it both ways.

What are your black boxes?

I hope I’ve convinced you that black boxes are everywhere. Now, I want you to think of your own life. What are your black boxes? We all have them, and my objective here is to get you to think about what they are.

At some point, we all hit a black box where we just don’t know how something works. This isn’t a bad thing. In fact, it’s a good exercise to see how deep you can go. Chances are, you won’t go far with most things. You will only be able to go deeper with the subjects you are passionate about. That’s okay and normal.

Now, think about your black boxes. Can you push past them and get a better understanding of the underlying mechanics? Pick a few that you want to get past, and start learning about them. Read a book on the subject, or ask a friend who is knowledgeable. I warn you that this is difficult, painful work. Understanding something isn’t a trivial task, so make sure you really want to learn.

You will know that you aren’t using a black box anymore when you can explain the idea or concept to someone who has no idea how it works. This is what you should strive for. If you can explain the concept (and not just recite it from a book), there’s a good chance you aren’t using a black box anymore.

This is my goal for education, both for myself and for the students I work with. My motto is “mathematics and science without black boxes”. More than anything, I want to help students understand what they are learning, not just how to use the tools to solve problems. The pendulum in education has swung too far in the direction of building skills without knowing the underlying concepts. My aim is to help nudge it back in the other direction.

There’s nothing wrong with building problem-solving skills. But we miss out on a large portion of the value of education when we only look to develop our skills. If you ask mathematicians, they will tell you some variant of “mathematics is art”. Many won’t tell you that they do mathematics to only solve problems in the world. Instead, it will be about gaining a deeper understanding. In essence, they are trying to push through their own black boxes. Why? Because they value knowledge in addition to solving problems.

Mathematics and science doesn’t have to only be about being skilled with tools. It’s an opportunity to inspect one’s black boxes, and work at opening each one up to peer inside.