Being Good At Mathematics

“How did you get so good?”

This is a question I’m asked from time to time with respect to mathematics and physics. People see the kinds of grades I get, and they want to know what my secret is. I presume they think I have a method, or at least some explanation as to why I get great grades at school. When I hear this question, I often have to hold myself back from ranting about what it means to be “good” at mathematics, and how I’m actually good at school. However, since this is my blog and we have the time to explore the nuances that are present, I want to lay out exactly what I think it takes to be “good” at mathematics.

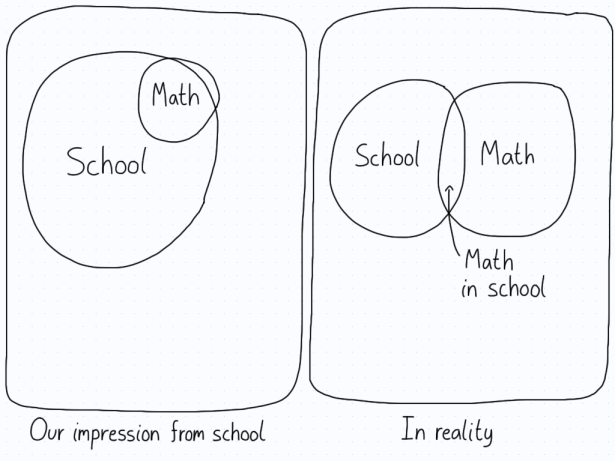

But first, I want to get something out of the way. If I ask you to give me five words you think of when I say “mathematics”, I’m betting that a sizeable portion of people would respond with “school” as one of their choices. This is important to realize, because it shows how we tie together two different concepts. On the one hand, we have school (and more broadly, the education system). This comprises a huge chunk of students’ lives, and involves a variety of disciplines. On the other hand, we have mathematics, which is a subject that’s taught in school, but only forms a small part of the experience. In this sense, many might draw a Venn diagram of school and mathematics like this.

The problem here is that mathematics is often fashioned as something that lives within the school system. As such, when we leave school (as many of us inevitably do), mathematics becomes a long-forgotten memory. The biggest drop-off occurs after secondary school. Once students start specializing in their degree for different careers, mathematics is often dropped. Therefore, the experience of doing mathematics remains as something that happens in school, and nowhere else.

The reason I bring this up is that this perception is an illusion. Mathematics is present in the entire world around us if we are willing to take a closer look. However, when we think of mathematics as something that is only done in school, we start to merge the two concepts together. As such, when people talk about me being good at mathematics, I think what they are really getting at is that I get good grades in mathematics in school. This seems like a subtle difference, but as I’ll describe below, there’s a huge chasm between being good at mathematics in general and doing well in school.

Of course, keep in mind that these are points I think are indicators of being “good” at mathematics. Different people might have slightly (or very) different ideas. I’ve listed these traits kind of implicitly, in the form of questions.

How resourceful are you?

To be good at mathematics, you need to be capable of using what you’re given to derive consequences. This is just a fancy way of saying you need to be able to use the axioms in such a way that you produce new results.

As time goes on, you’ll see that there are basic techniques that can be used to great effect. These include the standard techniques of proof (contradiction, induction, and so on), different tools from a variety of disciplines, and general “trends” that certain problems take. For example, if I’m dealing with a problem in the field of graph theory, I know that most of the results will have to use induction in some sense (though not always). Being able to reach back to what you learned previously can be a huge help.

This brings me to something which I’m sure will be controversial: memorization is often a good thing. I’m not talking about memorizing every mathematical fact you come across, but being able to remember a core set of facts can be of enormous help. I know, everyone likes to say that mathematics is all about being able to work out knowledge from first principles, but I think it’s evident that recalling facts can speed up the process. This is just as true in a test as it is when you’re working out a problem on your own. I guarantee you that basic memorization does make people think you’re “good” at mathematics (though it’s not critical).

Also under the umbrella of resourcefulness is the need for creativity. I think someone is “good” at mathematics when they look for creative solutions to problems. Creativity is a cornerstone for coming up with new proofs and finding new insights to old concepts. If mathematics is about understanding structures of some kind, creativity allows you to wander around these structures and view them from different angles.

Do you sit with an idea that you’re struggling with, or do you move on?

The “best” people at mathematics are those who refuse to skip over their ignorance. If they get to a problem that they don’t know how to solve or are confused about a concept, they don’t just commit it to memory and move on. Instead, they reflect about the idea and try to figure out where their misunderstanding lies. This is a hugely important point that I don’t think gets made enough. Willing to be stuck is key if you want to understand something new.

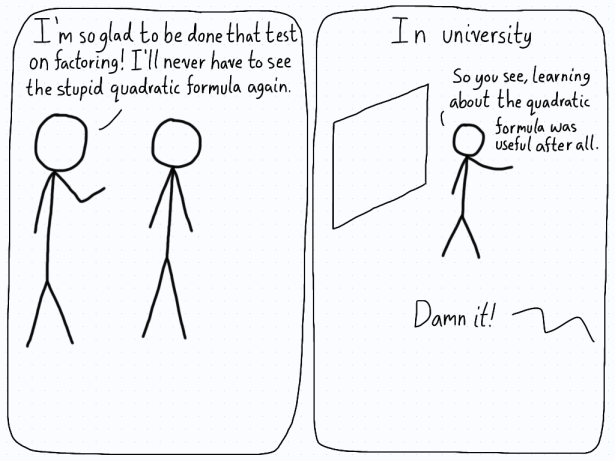

Learning mathematics is in large part about building a strong foundation. Once you have a strong foundation, you can increase the abstraction and complexity. Learning new ideas becomes easier. On the other hand, if you just skip over an idea that you don’t understand and commit it to memory in order to pass, it will come back to haunt you later on. It’s almost an inevitability, since mathematics is about accumulating knowledge on top of itself. To get to the “next” level, you need to understand what you’ve looked at previously. If you aren’t willing to sit with an idea you’re struggling with, you’ll find yourself on a shaky foundation later on.

The truth is that you will find yourself stuck later on, so it’s a good idea to build up your resilience from the start. If you aren’t willing to sit with uncertainty and figure out your confusion, the result will be a lot of frustration and not many problems solved. Mathematics is a process of being wrong over and over again until you’re finally right. As such, failure isn’t something to be avoided. It’s part of the deal.

How much persevering will you do?

This brings us to the idea of perseverance. If you want to be “good” at mathematics, you can’t give up when you’re learning. There will be setbacks and challenges, but they are all surmountable as long as you make a commitment to learning just a little bit more every day. If you go in with the mindset that everything should make sense on the first read through, you’re deluding yourself. It’s much more likely that you won’t understand a thing at first. Then, with a lot of work, you can slowly improve and wrap your mind around a subject.

When people tell me that I’m “good” at mathematics, what they’re commenting on is my ability at this particular part of mathematics. There are many more concepts within the subject that I haven’t wrapped my head around yet, but other people don’t see that. When we say someone is “good” at an activity, we probably aren’t thinking about it in an absolute sense. Instead, we look at their accomplishments and achievements in this specific instance, and generalize from that.

Being “good” at mathematics is not about solving problems quickly

This is an unfortunate result of our school system, and it’s something I want to talk about until everyone is sick of hearing me say it. You don’t have to solve problems quickly in order to be good at mathematics. If you think you need to be quick, you’ve been taught a bad lesson from the society around you.

Now, am I saying that there’s no utility to doing things quickly? Of course not. On a practical level, being quick at mathematics gives you more opportunities later on. After all, if you can work through problems quickly, you will have an easier time finishing tests and doing well. This will lead to external indicators that you are “good” at mathematics, which will in turn reinforce the idea that mathematics is your “thing”. As such, I would definitely say that being quick can help you, but I would argue against the idea that you need to be quick to be good.

If I think back to the moments where I most enjoyed learning about mathematics, they weren’t where I blazed through some reading and absorbed a bunch of ideas in a small amount of time. Instead, they were when I sat down and worked slowly through some difficult problems. After having a flash of insight and understanding the problem, that’s when I enjoyed mathematics the most. Trying to have this experience over and over again is what I would argue has made me “good” at mathematics.

Do I have some kind of genetic predisposition for mathematics? Maybe, I don’t know. What I do know is that any predisposition pales in comparison with the actual work required to go beyond talented and become good.

These were just a few cores ideas I’ve been thinking about in relation to being “good” at mathematics. I personally don’t like the discussion around being “good”, because I think it’s (mostly) a function of the effort and work you’re willing to put in. Sure, you may not be good in an “absolute” sense, but I think you can always improve with respect to your past self. If you learn about a new idea, you’re advancing your understanding of mathematics. It doesn’t have to be a groundbreaking new idea, just something that interests you.

This implies that improving in mathematics is an inevitability, if you’re willing to take the time to understand. Really, it’s a question of how committed you are to learning. I realize that there are extraordinary circumstances which don’t conform to this idea, but I think there’s still a broad applicability. That’s why I don’t like to use the word “good”. I much rather talk about the time a person has invested, since that indicates how serious they are and how much experience they have. I think these are much better indicators of ability in mathematics than just being “good”.

Hopefully, this changes the way you think about how people are skilled in mathematics. Remember, there’s “good” in the sense of school, and “good” in the sense that I explored here (invested time and effort). Overall, I think the latter better encapsulates the spirit of mathematics than the narrow, school-focused one.

Finally, I just want to make it clear that I am by no means “good” in the sense of professional mathematicians or even compared to high-achieving students. As always, when someone takes a judgement about being “good”, they are implicitly referring to a relative scale. Therefore, when I talk about being “good” at mathematics, I’m not trying to imply I am good with respect to those who are the best in their field. Rather, I’m comparing myself more to the average person.